A liberator’s tale: ‘In my nightmares the scenes recur’

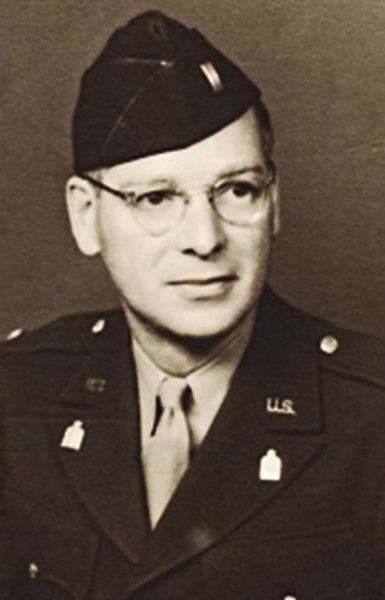

When we hear the name Eli Bohnen, many people in the community fondly recall the long-serving rabbi of Temple Emanu-El. They remember a gentle and compassionate man who was considered a rabbi’s rabbi, and speak of B’nai Mitzvot, weddings, sermons and his service to our community. During his career at the Providence temple, 1948-73, Bohnen touched the lives of thousands of Rhode Island’s Jewish families.

But there was another side to Rabbi Bohnen, a side that many people may not know about. He, and Rabbi David Eichorn, were the first Jewish chaplains to enter the Dachau concentration camp. They arrived at Dachau, in Germany, on April 30, 1945, the day after the camp was liberated.

As Bohnen’s daughter, Judy Levitt, relates, “Originally from Toronto, my father was serving in another Temple Emanu-El, this one in Buffalo, New York. When the war broke out, he volunteered to go over as a chaplain. About a year after he returned, we moved to Providence so he could become the rabbi at our Temple Emanu-El.

“During the war, he wrote beautiful love letters to my mother. He was a real romantic, which people may not realize. He also wrote beautiful letters to me, even though I was only two years old at the time, some of which I still have.”

Chaplain Bohnen was assigned to the 42nd Infantry Division, known as the Rainbow Division. They landed in Marseilles, France, in December 1944 and pursued the Nazis through France, Germany and Austria before helping to liberate the concentration camp at Dachau.

Dachau was the first Nazi concentration camp, created in 1933, and was a model for the camps that followed. It was one of the last camps to be liberated.

When the U.S. Army reached Dachau at the end of April 1945, they found more than 30 railroad cars filled with the bodies of prisoners who had died of starvation en route. Upon entering the camp, they found about 32,000 prisoners: Some 1,600 individuals were crammed into each of 20 barracks that had been designed to house 250 people.

“Just like many survivors, he didn’t want to talk about it for a long time,” Levitt says of her father who died in 1992. “My brother remembers a sermon he gave about it, but just when survivors were really beginning to talk more about their experiences, my dad became ill.”

Although he may not have spoken much about what he encountered, Bohnen’s writings detail the horror of Dachau. On May 1, 1945, two days after the liberation, he wrote in a letter to his wife Eleanor: “Nothing you can put into words would adequately describe what I saw there.

“The human mind refuses to believe what the eyes see. All the stories of Nazi horrors are underestimated rather than exaggerated. We saw freight cars with bodies in them. The people had been transported from one camp to another, and it had taken about a month for the train to make the trip. In all of that time they had not been fed. They were lying in grotesque positions, just as they had died.Many were naked, others in thin clothing. But all were horrible to see”.

“We entered the camp and saw the living. The Jews were the worst off. Many of them looked worse than the dead. They cried as they saw us. I spoke to a large group of Jews. I don’t remember what I said, I was under such mental strain, but Heimberg (my assistant) tells me that they cried as I spoke.

“Some of the people were crying all the time we were there. They were emaciated, diseased, beaten, miserable caricatures of human beings. I don’t know how they didn’t all go mad. There were thousands and thousands of prisoners in the camp. Some of them didn’t look too bad but most looked terrible. And as I said, the Jews were the worst. Even the other prisoners who suffered miseries themselves couldn’t get over the horrible treatment meted out to the Jews.

“I shall never forget what I saw, and in my nightmares the scenes recur. When I got back I couldn’t eat and I couldn’t muster enough energy to write you.

“No possible punishment would ever repay the ones who were responsible ....”

According to Levitt, “My dad stayed in Europe for another nine months working in a displaced persons camp in Austria. With a wife and child at home, I think he felt it was his obligation to help these people.”

She added that she worries that, “There are so few survivors left at this point, who is going to be telling this story?” And, she said, if people don’t remember, it could happen again.

The Sandra Bornstein Holocaust Education Center, in Providence, has items from this period in Rabbi Bohnen’s life. Visitors are invited to come to see these artifacts, and to learn more about the Holocaust and Bohnen’s role as a liberator.

Much of the information for this article was provided by Levitt’s brother, Michael Bohnen, who culled it from a variety of sources.

LEV POPLOW is a communications and development consultant who writes for the Sandra Bornstein Holocaust Education Center, in Providence. He can be reached at levpoplow@gmail.com.