Gone but not forgotten: Jewish delis, bakeries and Benny’s

The conversation began with the red sticker on the box containing a hand mixer. Printed on the sticker was the price and the name of the store – Benny’s. Seeing the familiar sticker led to a lament for our favorite store from days gone by, where you could always find what you needed (and sometimes did not even know you needed until you found it there).

The conversation then shifted to some of the many conveniences once taken for granted, but now gone from our lives: sending your child to the nearby A&P for a few items, shopping for children’s clothes at Susan’s and shoes at Lad & Lassie on Hope Street, buying meat at a Kosher butcher shop, knowing that sissel bread was always available at a nearby Jewish bakery.

Sadly, today we can no longer buy a rolled beef sandwich on sissel and a bottle of Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray tonic to go with it.

Ah, rolled beef! In my youth, that epicurean delight had a place in just about every Jewish deli. Although akin to pastrami, it differed in important ways. The cut of beef was usually the same, as were the basic spices, but after it was cured and spiced, it was rolled and smoked – and each deli’s chef had his own secret addition. (Rolled beef also differed from Montreal smoked meat. The Montreal delicacy uses a different cut of meat and can be heated. Rolled beef is never served hot.)

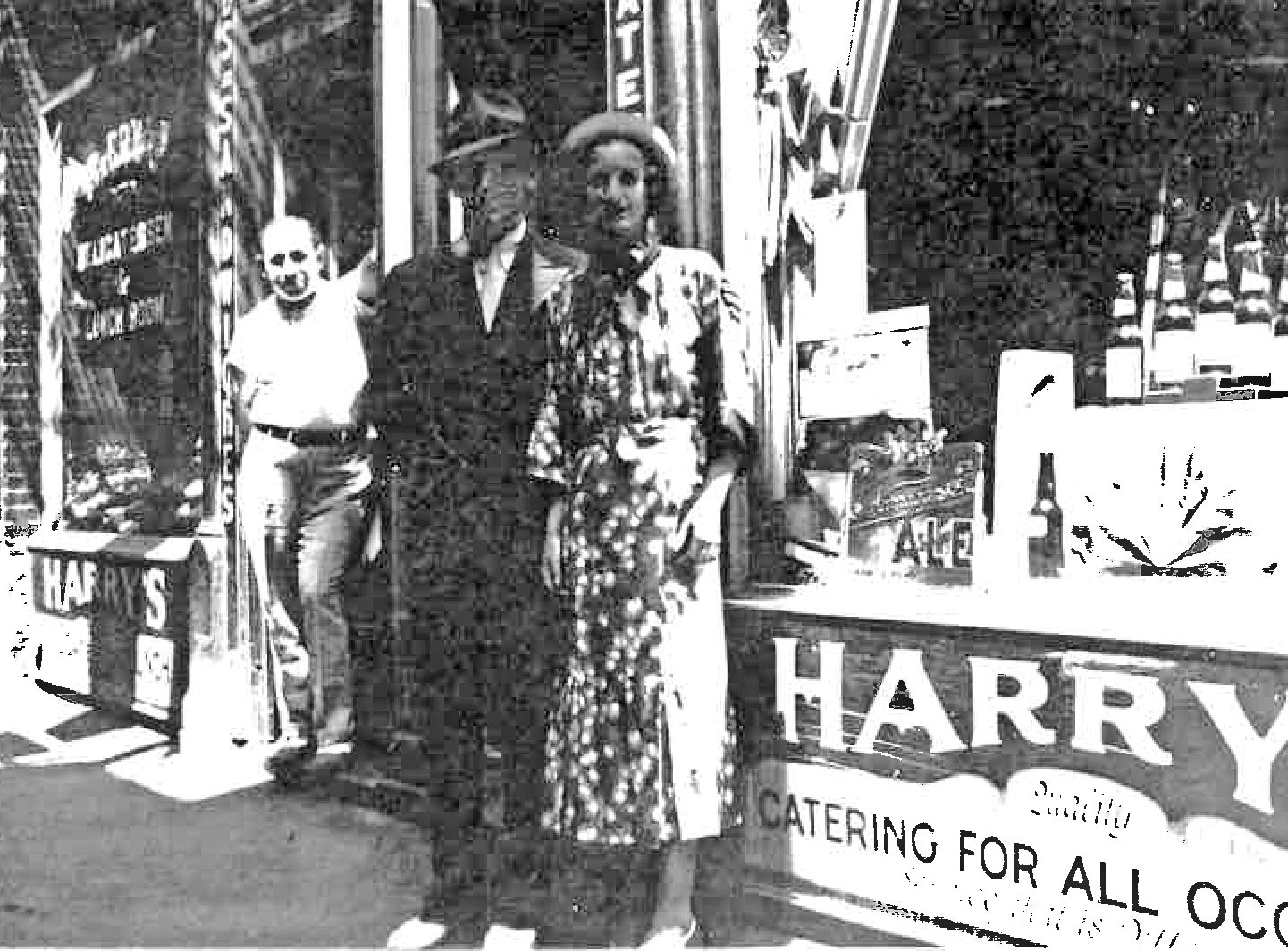

All the delis made wonderful sandwiches for takeout. But if you wanted to sit at a table and leisurely enjoy your choice, perhaps with a side of potato salad or a knish and a pickle from the barrel in the backroom, you went to a deli/restaurant like Cohen’s, a popular, pleasant gathering place in Providence’s North End, or Harry’s in “Pie Alley,” as Clemence Street was known at the time, perhaps because of its many restaurants.

Harry’s, at 90 Clemence St., though lacking in curb appeal, attracted business people and shoppers. It was also a place to go at night, after a movie or a sports event, since it was open late. The décor was best described as utilitarian, with nondescript white tables and wooden chairs.

If I were just writing about food and ambience, this article would end here, but my research assistants (my daughter Judith and Jaime Walden at the Rhode Island Jewish Historical Association) found this related bit of World War II history, an individual’s war effort and a bygone era.

During the war years, Harry’s became a “downcity” mecca for soldiers and sailors on leave. What made Harry’s special for them was not Kosher deli, whose delicacies were unknown to most of them. The attraction was the proprietor, Harry Mincoff, whose generosity extended far beyond a free meal. From his own service in the Navy during World War I, Mincoff knew what it meant to be lonely and without funds in a strange city.

Mincoff was a colorful character. He had a round ruddy face, with a cigar usually in the corner of his mouth. He was “A balding Mr. Five-by-Five … with a cluster of three big diamonds on one hand [and], say Dallas ex-servicemen, gold in his heart,” according to an article printed in The Dallas News and reprinted in The Jewish Herald in March 1946.

None of the servicepeople who came to Harry’s ever went away hungry or broke if Mincoff could help it. If he noticed a soldier or a sailor who seemed lonely or troubled, Mincoff sidled over, eased into a chair and began to chat. An avid sports fan, Mincoff could speak knowledgeably about a whole range of sports topics. He engaged his companion in seemingly casual conversation. Once he knew the nature of the problem, Mincoff would open his wallet or find a way to ease the loneliness or other problem.

Mincoff invited his patrons to put their spare change or a donation of any amount into a special jar near the cash register. He also added large sums of his own. The money was then made available as loans to servicepeople in need of emergency funds – no questions asked nor repayment requested; it was all on the honor system, with no records kept.

The news about Harry Mincoff and his jar soon spread among the soldiers and sailors stationed nearby. Mincoff would later say, with pride, that almost all the loans were repaid.

After the war’s end, Mincoff went on a coast-to-coast trip to reconnect with the many service members he had hosted at his restaurant. Texas was one of the many places welcoming him.

Now, what about that wonderful sissel bread of yesteryear? In Rhode Island, our sissel story began in 1891, when Samuel Schechter opened the first Jewish bakery in our state, in the North End of Providence. From that date until 2000, 21 Jewish bakeries were established in Rhode Island, mostly in Providence, but also in Woonsocket, Central Falls and Cranston.

In the early years of the previous century, many bakers, after they had finished their own baking for Shabbat, allowed neighborhood women to use the big ovens to bake their own challah, and to even sell any extra loaves. This was a carry-over from a European tradition.

Only one Jewish bakery is left to make the delicious Jewish rye breads we remember, the Rainbow Bakery in Cranston. On my behalf, Gerald Sherman asked Murray Kaplan about the bakery’s unusual name. In 1954, Murray Kaplan’s father and his partner, Al Brody, purchased the bakery. They could not decide which family would get to name the shop. Since the movie “The Wizard of Oz” was very popular then, they compromised by choosing the name Rainbow.

GERALDINE S. FOSTER is a past president of the R.I. Jewish Historical Association. To comment about this or any RIJHA article, contact the RIJHA office at info@rijha.org or 401-331-1360.