We are all campers

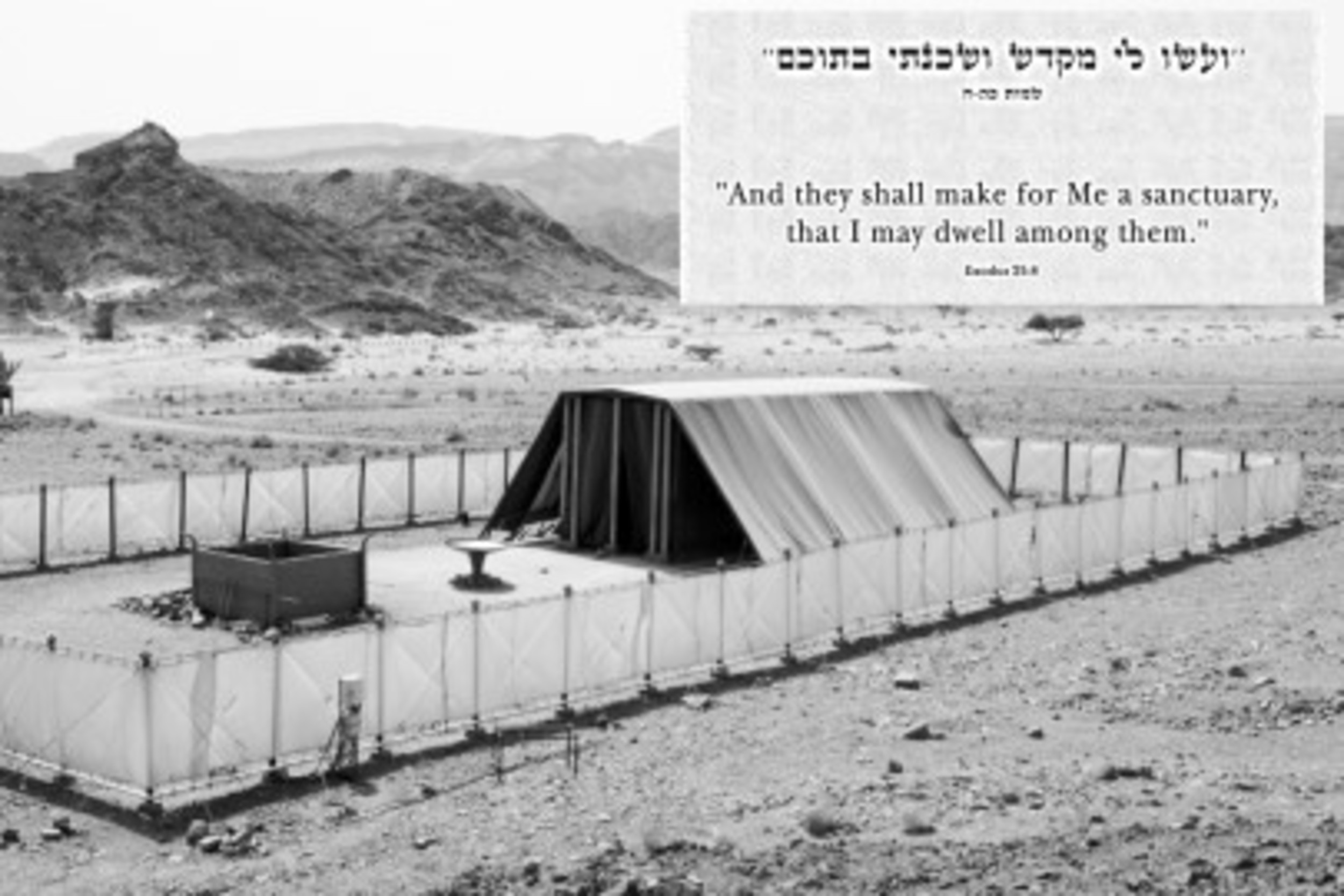

As we approach the final chapters of the Book of Exodus, we read of the concluding stages of the construction of the Mishkan, the Sanctuary which our people carried with them through their desert wanderings.

With exquisite care and almost infinite detail, the Torah describes and measures each piece of material and each stretch of fabric. The result was a masterpiece of construction: a portable sacred space which embraced an entire nation. No less remarkable is the fact that the entire structure was constructed of materials that they had with them. There were no textile manufacturers, precious metal purveyors, or lumber yards. Yet our wandering ancestors somehow found—and gave—all that was needed to produce the very first Israelite House of Worship: a Holy Place where they could find and express their relationship with God.

Since this is the time of year when parents begin to think of “camp” for their children, it seems only fitting that we stop and consider what the Mishkan and its construction can teach us about camping—and about ourselves. “Camping” is not merely an activity, something we or our children do. Camping is about who we are. Some of us camp, and some of us do not. A younger relative of mine attended an excellent Jewish camp in California. Her summer was filled with wonderful Jewish community, activities and learning. But judging from the accommodations, one might think it was a resort for Jewish teenagers. Not much by way of the more “rustic” settings those of us from another generation might recall.

I have had the pleasure of being the Rabbi/Chaplain of the Yawgoog Scout Reservation for the past 13 years. Yawgoog is much more than a place where people have camped; it is, for those who have been there, a state of mind. At Yawgoog, children and adults of all backgrounds learn about each other—and more importantly themselves.

A hike becomes more than a walk in the woods on a trail with colored markers. It is a place to experience the wonders of Creation, and to feel the presence of the Creator of All Things. A night under the stars opens the heart to the awe and majesty of the universe, and the One Whose Word brought it into being. At Yawgoog, a Jewish boy can study, pray, read Torah, prepare for and celebrate becoming Bar Mitzvah in the Camp Synagogue—the Temple of the Ten Commandments. At Yawgoog, perhaps more than during “real life” one can experience the sacredness with which creation has been endowed. To “camp” at Yawgoog is to make a brief but indelible stop on one’s spiritual journey. No one leaves unmoved or unchanged.

At Yawgoog, too, the “accommodations” have changed from the time when troops slept in pup tents on bare ground, cooked over open fires, hiked, “dwelt” in the woods for a few days, supplied only with what they could carry in their knapsacks and whatever else they could haul in. It is still “rough-hewn,” but the lessons of camping remain, teaching us much about who we are as people, and as A People.

We Jews are quintessential campers. Camping is in our history. It is written on the pages of the stories we transmit to our children, and the histories we pass down to future generations. We have “camped” from Ur of the Chaldees to the desert floor of Jacob’s night dream, from Egypt to Exile. We have “camped” in countless places, always awaiting the moment when we would return home. Camping is not about the permanent. It is about the temporary. It is about exchanging the comforts we know for a brief sojourn in the unknown, the uncomfortable, the spiritual—the Sacred. It is about shifting the complacency of who we are sure we are to the discovery of what we never knew about ourselves and what we can accomplish.

We are quintessential campers. From the days of the Mishkan, we have come to understand that our history would be one of many peregrinations. We were destined to “camp” in many places. Some hospitable and friendly. Some angry and hate-filled. Some were nurturing and inviting. And some caused us unimaginable harm. Throughout all of them, we knew, somehow—or we came to know despite ourselves—that we were always only “campers.” Looking into our sacred texts, we can see how the Mishkan simply taught us some of the lessons we would need to know as sojourners and “campers” in this world.

Lesson 1: Carry what you need.

But only what you need. You will need everything you carry. But you cannot take more than you can carry. Remember, you will only have what you take.

Lesson 2: You will be tested, challenged, and sometimes tormented.

You will be cold, hot, hungry, wet. You may need to pack up and go on a moment’s notice. You will have to take it all down and transport all that you have and all that you are in the blink of an eye. So only take what is sacred and special with you. Wherever you are, wherever you land, will shape you, mold you, and teach you about what you are capable of

Lesson 3: Wherever you are—God is.

Look around at your surroundings. Take them in. How can you not be awed by what you see and feel? Know that wherever you are--wilderness or palace—is a small piece of Divine handiwork. Take the moment to comprehend how filled with wonder is the place where you stand.

Lesson 4: Wherever you are, God can be.

Wherever you rest your head--on a down pillow or a desert rock--there is a gateway to Heaven. You have the ability to carry and build your own sacred space wherever you are. The Mishkan came down and went up in short order. It has taught us that wherever we “camp,” there we can build our sanctuary. There we can find time and space for the sacred, to experience the numinous, and the Divine. The Jewish people survived because they learned to carry their Mishkan with them—in all of its many forms.

Lesson 5: Know, that wherever you are, whatever you have, you can build that sacred space—your own Mishkan—out of whatever is at hand.

The precious metals of your thoughts, the fabric of your dreams, the boards built out of the work of your own hands are the tools you will have.

Camping is a state of mind. The Mishkan is a state of being. It is the repository of the spiritual memories of our people and their wanderings. We read of the human generosity, devotion, and design which brought it into our lives. But beyond all of that, beyond the gold, tapestries, and the marvelous engineering, the Mishkan directs us to eternal truths about ourselves: that our real needs are few, that wherever we stand we are in the presence of the Holy, that out of whatever is at hand we can build our sanctuary—our sacred space, and there, as always, we will be in the presence of God.

RABBI SOL GOODMAN (rabbisol1@aol.com) is the long standing Rabbi of Sister Congregations Temple Beth Shalom of Milford and Congregation Ael Chunon of Millis, Mass., Chaplain at the Norfolk County Sherriff’s Office and Correctional Facility, Mass. and Senior Chaplain of Yawgoog Scout Reservation in Rockville, RI.