Review: A glance into an alternate universe

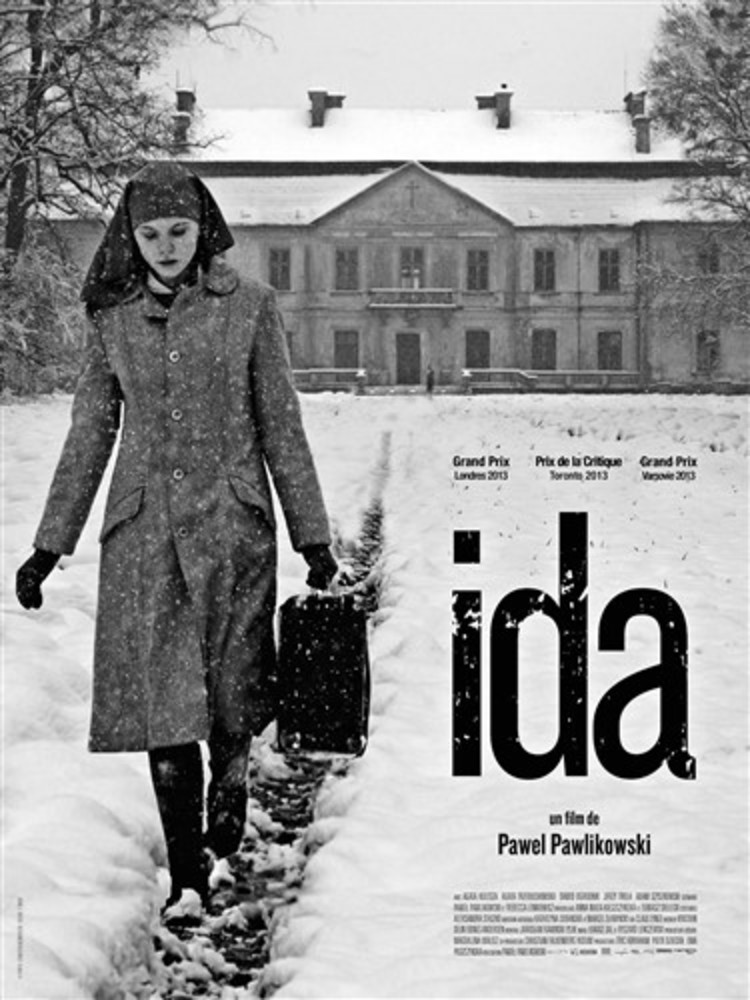

Ida leaving the monastery to meet her aunt.

Ida leaving the monastery to meet her aunt.

If you enjoy spending hours strolling through photo galleries and reading the captions, see “Ida.” If you think Edward Hopper’s paintings are beautiful, see “Ida.” If you don’t mind not knowing enough about the characters to understand why they choose what they choose, see “Ida.”

Those who watched the Oscars and expect the film to be as clever and witty as Pawel Pawlikowski’s acceptance speech for the Best Foreign Language Film might be disappointed. Yes, the movie has garnered high praise from critics worldwide. Yes, it’s unusual and artsy and charming. It’s also unnecessarily slow, unfortunately incomplete and unnervingly unmoving for the most part, considering the subject matter.

Pawlikowski seems to rely on cinematography to fill the gaps in the story, character development and historical background. However, even that method is somewhat flawed considering the language barrier. If you’re forced to read the subtitles, you might miss the essential element of the film – the bare beauty of the imagery.

Anton Chekhov has said, “Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.” In this compact and understated 82-minute movie about a novitiate in 1960s Poland, Pawlikowski removes not only the rifle, but also the nail it was hanging from, as well as the wall and the house. All that’s left is the scenery and your imagination.

Ida, an 18-year-old who was raised in a convent and knows nothing about her family, is not particularly interested in learning about her roots. When Mother Superior tells her that she has an aunt, Ida agrees to visit her only because she has to. After all, Ida’s allegiance is to Jesus – we see that from the very beginning of the film in a scene where Ida is cleaning his statue and helping to place it on a pedestal. Standing in for family, Jesus provides comfort when Ida needs it. She kisses the cross on her chain when she has trouble sleeping. She relies on Jesus to watch over her as she is packing her suitcase. She prays to him on her knees when she encounters his likeness during travel.

Nevertheless, Ida leaves the serenity of the convent for the chaos of the city. Rushing trains replace vast fields. Briskly walking passersby contrast with the novitiates who lie prostrate on the ground, praying. Ida’s movement is significant here as well. In more than one scene, we witness her walking up stairs. She is shown ascending when she is following Mother Superior’s orders – walking away from a meeting, determined to visit the aunt, and walking toward the aunt’s apartment.

Wanda, the aunt, is an austere woman of few words. She feels no shame at having a man in her bed, wearing a robe in the middle of the day or not having picked up Ida from the orphanage. Refusing to reveal any details, Wanda speaks in curt statements that don’t invite dialogue. Her responses bear a hint of annoyance at having been asked in the first place. It’s no surprise that Wanda chooses not to soften her disclosure that her niece is “a Jewish nun.”

This jaded Nazi resistance fighter and Communist party member eschews emotion, acknowledging only hard facts. The consequences of her vices don’t concern Wanda; Pawlikowski illustrates that with every pothole the drunken woman hits. As the two of them drive to the village in hopes of learning what happened to Ida’s parents, Wanda feels it’s her duty to instill some sense into Ida by suggesting that the vows she’s about to take would be more meaningful if she knew what she was sacrificing. The words stay with the niece.

Upon Ida’s disapproval of Wanda’s straying from their goal, the aunt sets her straight by uttering the sole redundant statement of the movie, “I’m a slut, and you’re a little saint.” She’s mocking Ida because she thinks her niece’s imminent choice will lead to a wasted life. Toward the end, Pawlikowski’s clichéd series of scenes prove that there are other ways to waste a life. The viewer wishes that Wanda had explored Ida’s point of view further and gotten herself to a nunnery.

However, the aunt is far from the type of woman who would listen to anyone, let alone God. Past prosecutor of “the enemies of the people,” Wanda demands answers despite her awareness of the fact that Poles are terrified to expose anything out of fear that the Communists will punish those who helped the Jews. Sadly, the director does not clarify this point for audiences who might be unfamiliar with the nuances of history and the fact that three million Jews were killed in Poland during the war.

Being around Wanda, Ida begins to inherit some of her brutality. Even though Ida rips the Bible out of Wanda’s hands, as if the latter is not worthy and might contaminate it, Ida is starting to feel curious about what else life has to offer. When she decides to listen to a jazz band performing in their hotel, she walks down a staircase for a change. It’s as if the director is hinting to us that this is the beginning of her descent into sin. Ida’s appreciation of a Coltrane cover is that rifle that’s about to go off.

Unlike the pretty jazz singer, who expresses herself through suggestive movements, loud makeup and high hair, Ida reveals her changing mindset with a barely perceptible smile upon being complimented. Later, as she stands in front of a mirror, letting her hair down, she seems to be trying to see herself in the same light as the man who gave her the compliment. She succeeds.

After her visit, Ida realizes that she’s no longer a naïve girl. In a telling succession of scenes, novitiates go about their monastic lifestyle in unison. As they’re eating, Ida suppresses a laugh – a misstep that earns her a punishing look from the Mother Superior. It’s reminiscent of the look Ida gives Wanda when the aunt questions her devotion. As everyone prays, Ida stands out again, silently staring into space. We realize Ida is wondering whether chastity, poverty and obedience are preferable to marriage, a house and children.

You’ll have to watch the film to find out what decision Ida makes. Unsurprisingly, the director lets us figure it out rather than show us a clear ending. He foreshadows the final scene with Symphony No. 41 – the last one Mozart composed. Possibly, Pawlikowski chose this piece of music to symbolize other lasts in this movie.