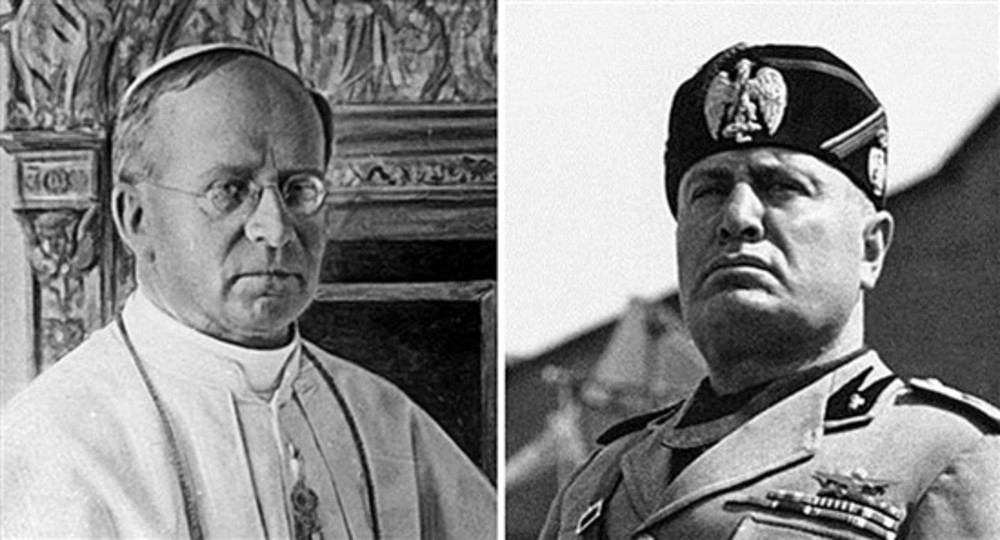

‘The Pope and Mussolini’

Pius XI served as pope from 1922-1939 and supported the Fascist regime with certain stipulations. Benito Mussolini was Italy’s prime minister from 1922–43 and achieved notoriety as a Fascist dictator.

Pius XI served as pope from 1922-1939 and supported the Fascist regime with certain stipulations. Benito Mussolini was Italy’s prime minister from 1922–43 and achieved notoriety as a Fascist dictator.

There are certain things you expect from a pope, and anti-Semitism is not one of them. In his latest book, “The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe,” Pulitzer Prize-winning author and Providence resident David I. Kertzer exposes the lives of two men – Pope Pius XI and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Their complex relationship, politicking and secrets changed the course of history.

Until the 2006 opening of the Vatican’s archives, much of Papal Rome’s association with Mussolini was speculative and controversial. Based on seven years of research in the Vatican and Fascist archives, Kertzer, a Brown University professor of Social Science and professor of Anthropology and Italian Studies, sheds light on the rise of Fascism and Natzism in Europe, as well as the alliance between the State of Italy and the Holy See.

Pius XI and Mussolini are described as polar opposites. The bespectacled pope, a former librarian, was erudite, pious, self-righteous, headstrong and reclusive. “Il Duce” (pronounced “eel DOO-cheh,” meaning “the chief” in Italian), Mussolini’s title for himself, was irreligious, egotistical, hot-tempered and a philanderer who came from peasant roots. At times, Kertzer portrays the pope as an unwilling participant in the game of politics and Mussolini as a man who bullied his way to leadership in the Italian Fascist regime. However, the unlikely partnership between these two men served both the Church and the dictator for nearly two decades. They relied on each other to achieve their doctrinal and political objectives. “We have many interests to protect,” Pius XI said shortly after Mussolini gained control of the Italian government in 1922. Although the two men only met once, they communicated steadily via Catholic envoys, political ambassadors, representatives from the press, spies within the Church and surreptitious go-betweens.

The pope played a central part in keeping the Italian dictator in power, and in exchange for Vatican support, Mussolini reestablished privileges the Church had lost, including mandatory religious education in schools and police enforcement of Catholic morality. Then in February of 1929, the signing of the Lateran Accords took place, sealing the fate for both men. The agreement, signed by the Italian Republic and the Holy See, recognized Vatican City as a sovereign and independent papal state with the pontiff as its recognized leader. In turn, the papacy declared neutrality in military and diplomatic conflicts of the world.

“To understand why the pope ended up embracing Mussolini you need to understand how embattled the popes of these years felt. … Mussolini promised to restore the Church and the clergy to a privileged position in Italy,” Kertzer told fellow author Jon Meacham in an interview. “The pope dreamed of making Italy into what he called a ‘confessional’ Catholic state and planned to use Mussolini to help him accomplish his goal. [The pope’s] greatest fear was that the socialists and communists would take advantage of the multi-party chaos to come to power in Italy. He saw Mussolini as the best bet for preventing it.”

Kertzer also uncovers that discrimination against Jews permeated the Catholic Church. The Pope told Mussolini that the church needed to “rein in the children of Israel” and to take “protective measures against their evil-doing.” As il Duce developed a close political relationship to Hitler during the 1930s, a perfect storm was brewing.

Whether Pius XI could have changed the course of history by denouncing the Nazi party, condemning the mass murder of European Jews, excommunicating Hitler or impeding Mussolini’s amassed power is subject for debate. What is known is that Europe would never be the same. As the Pope’s health failed and his trust in the European government diminished, Mussolini’s popularity grew to demi-god status. For both pope and politician, their worldview was challenged, and each man was desperate to see his agenda carried out regardless of the cost.

Publishers Weekly called “The Pope and Mussolini” a “fast-paced must-read,” and the San Francisco Chronicle describes the book as “the real ‘Da Vinci Code.’ ” The Pope’s relationship with the Fascist leader is told in a historical and vivid way. Kertzer creates distinct biological sketches of Pope Pius XI and his chief cardinals, Mussolini and the men who helped enable the reign of Fascism in Italy; and the many women who dallied with Il Duce. With such a tremendous number of players, Kertzer includes a “cast of characters” section at the beginning of the book to reference.

The historical subject, scholarly approach and number of pages (592 total) may intimidate the average reader, but do not fret. The book reads like a novel, with each page begging to be turned. Kertzer magically weaves chronological context, hamartia, intrigue and even some sexual tension into this biopic gem.

KARA MARZIALI is the director of Communications for the Jewish Alliance of Greater Rhode Island and an avid reader.