‘Wiesenthal’

Can a slim 53-year-old Irish Catholic with a full head of hair convincingly portray a stocky 92-year-old balding Jew? If that seems improbable, add to the challenge an Austro-Hungarian dialect and a shaky tremor. If your answer is “highly unlikely,” think again.

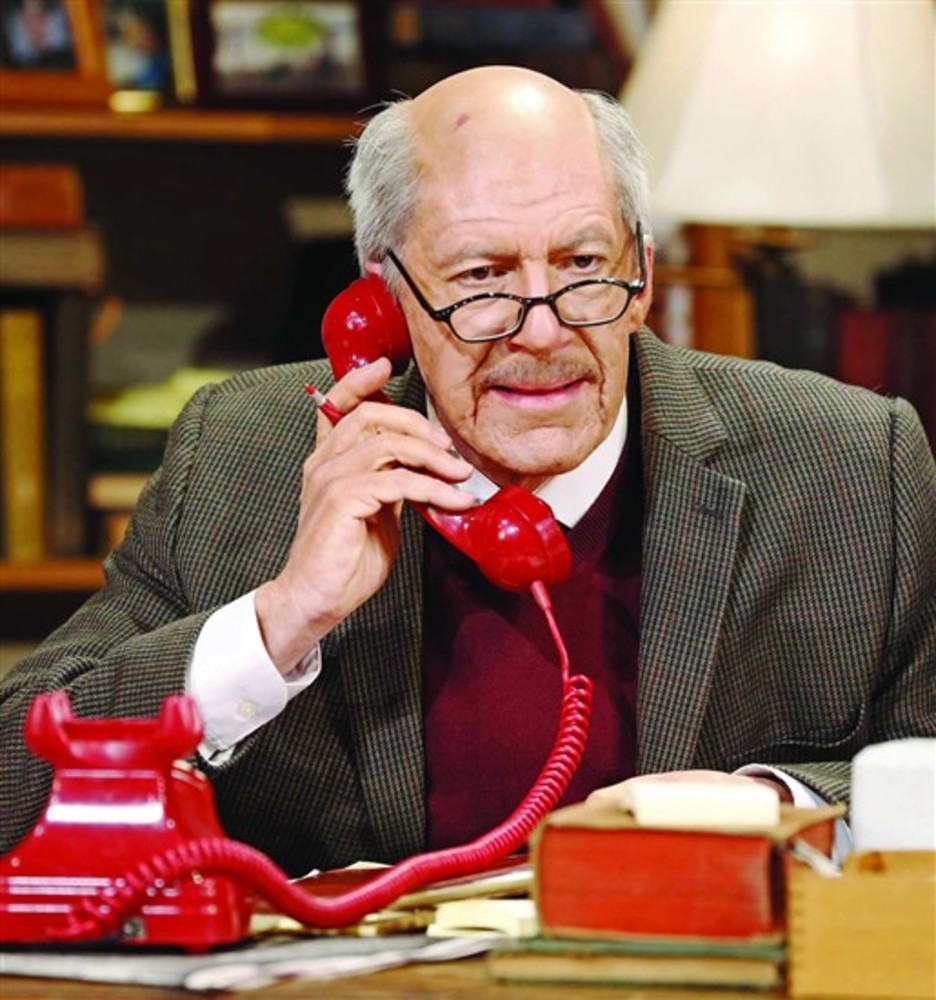

Tom Dugan, who wrote and stars in “Wiesenthal,” does just that. He knows that the illusion is successful because, when he returns to the stage for a Q-and-A, the audience assumes he’s a janitor. To reach mastery over his character, Dugan not only completely overhauls his appearance – by shaving his head, wearing a padded suit and putting on old-age makeup – but also transforms his speech with the help of a dialect coach. To mirror the Nazi Hunter’s gestures and to illustrate the feebleness of age, Dugan wipes his eyes with a handkerchief, steadies himself by pulling on furniture and struggles to maintain balance.

Dugan, who grew up in Winfield Township, New Jersey, and studied theater at Montclair State University, has been acting professionally for a quarter of a century. Having written plays for the past 15 years, he’s known for his six one-man shows, one of which is a one-woman show and the most famous of which is “Wiesenthal.” In fact, it is so popular that PBS is creating a special with the same title.

Dugan decided to write the play to honor his father’s participation in World War II. A Langenstein-Zwieberge concentration camp liberator and recipient of the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart, Dugan’s father served as inspiration.

In addition, Dugan says that he wanted to carry on Wiesenthal’s message of tolerance, which hits a strong chord with him. He chose this particular format because of the intimacy which the dialogue creates, stimulating the audience’s imagination.

Dugan’s ability to affect is evident in interviews conducted right after the performance. One viewer explains his appreciation of the play by saying that “the show gives words for people who still have a hard time talking about [the Holocaust].”

By watching the spectators’ reactions, the actor is able to fine-tune his craft, keeping the show fresh. He says that the audience’s response constitutes the most surprising element of the play. Dugan had no idea how potent the piece would turn out. It’s not unusual for him to receive letters from people who saw the show five years ago and now want to share its effect.

Dugan sees the sustainability of the message as a measure of success. He is not the only one who recognizes the value of “Wiesenthal.” In March, Dugan received a letter informing him that he is the newest recipient of Seton Hall University’s Sister Rose Thering Humanitarian Award.

While he’s proud of the honor, Dugan didn’t envision the play for the accolades. He is a strong believer in following his parents’ generation in its quest to keep youth informed about the past. Dugan says, “It’s incumbent on us to pass on those lessons.” Of course, the challenge is that his generation didn’t experience the Holocaust. That’s why he wrote the play – to make horrid and foreign stories palatable to young people, who are easily bored. Like Wiesenthal, he uses humor to achieve this feat.

Dugan set the show in Wiesenthal’s office on the day of his retirement. Because the survivor was captivating, thousands of teens from around the world visited him to hear the tales. During the play, the audience becomes a final group of visitors, absorbing his knowledge and reacting to his wartime suffering. Dugan hopes that his performance captures Wiesenthal’s skill of keeping youth engaged despite the darkness of his message.

So far, this has been the case. Dugan says that the audience doesn’t start out enthusiastically, given the subject matter, but end up on their feet, cheering, by the end of the performance. He tells about a Goth girl he noticed in the first row during a matinee. Observing her initial negative demeanor, he said to himself, here’s one audience member I’m not going to reach today. To his surprise, the girl came back for the evening show and, this time, brought her family along. Dugan thinks that the topic appeals to those who consider themselves a minority. After all, Wiesenthal’s message was universal. He didn’t just fight for the Jews. He fought for the gypsies, the homosexuals, the mentally ill – all the underdogs.

To prepare for writing, Dugan started his research at the Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles in 2007. Just as Wiesenthal spent 60 years gathering evidence of the Nazis’ atrocities, Dugan gathered evidence of Wiesenthal’s heroism. By ’08, he had read enough archives to begin “workshopping” with Jenny Sullivan, the director. The two of them forged a means to bestow hard, essential information in an entertaining manner.

Consider what the playwright and the director had to work with: their only character is a man who survived the unthinkable – Hitler’s genocide – and dedicated his life to preventing any future occurrence of it. In an interview, referring to the way the Holocaust changed people, Wiesenthal says, “We [lost] every [belief] in humanity and friendship and justice.” Despite his incarceration in a concentration camp, separation from his wife and loss of 89 family members, Wiesenthal maintained hope and the will to live to correct the injustices.

In “Genocide,” a 1982 documentary, he explains his perseverance with his quest. When journalists question him as to why he keeps tracking the Nazis, having discovered 1,100 of them already, Wiesenthal responds that he cannot close the office because it is the last office. Along the same lines are Sir Ben Kingsley’s recollections of his meeting with Wiesenthal in preparation for “Murderers Among Us: The Simon Wiesenthal Story.” In an interview, the actor remembers seeing documents on Wiesenthal’s walls, proof of atrocities about which the survivor said, pointing, “This is blood turned to ink.”

To carry on the memory of those lost lives, Dugan continues performing. In doing his research, he found himself having a hard time reading the material. The more he learned about the Jews’ experiences, the more breaks he had to take. The horrors overwhelmed him, forcing him to seek refuge in innocence. Dugan would put the books down to sit on the floor with his two young Jewish sons (he married a Jewish woman). As he would hold the kids on his lap, he would slowly start to refocus his thoughts on the good – on feeling grateful for the fact that his kids were born now and not then.

Yet, after a dose of sunshine, Dugan would go back to the gloom to ensure that it never happens again. A note he reads during the play explains clearly why Wiesenthal continued his search and why Dugan finished his play. “Do not pity me. Now that you have read this letter, I am no longer dead. I live in your heart. Please promise that you will never forget me.”

IRINA MISSIURO is a writer and editorial consultant for The Jewish Voice.

The facts:

The Zeiterion Performing Arts Center in New Bedford is presenting “Simon Wiesenthal”on Holocaust Memorial Day

There is a free The Z’s pre-performance book club discussion of “Branded on My Arm and in My Soul, a Holocaust Memoir” by Abraham W. Landau.

When: Thursday, April 16

8:00 p.m.

Where: 684 Purchase St.,

New Bedford, Mass.

Call 508-994-2900

Tickets: $20/$25/$29