An ordinary mother’s letters and poems tell of the heartbreak of life under the Third Reich

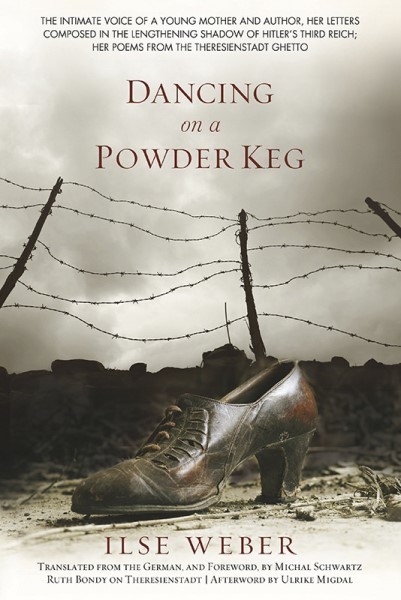

“Dancing on a Powder Keg: The Intimate Voice of a Young Mother and Author, Her Letters Composed in the Lengthening Shadow of Hitler’s Third Reich; Her Poems from the Theresienstadt Ghetto,” by Ilse Weber (translated from German by Michal Schwartz). Bunim & Bannigan. 340 pages. $34.95

It is unlikely that you have ever heard of Ilse Weber. But once you know her story, her name will be seared into your heart.

“Dancing on a Powder Keg,” released this month in English (released in 2008 in Israel), is Weber’s story, told almost exclusively in her own words. Weber was a Czech woman – a wife, mother and musician who also wrote plays, books and poems. She was murdered in Auschwitz in 1944 along with her youngest son, Tommy; she insisted on being deported along with her husband (who survived) and the children she cared for in the children’s sickroom in Theresienstadt (who did not survive).

The main focus of “Dancing on a Powder Keg” is letters Weber wrote between 1933 and 1944 to her childhood friend, Lilian von Lowenadler, and Lilian’s mother, Gertrude. They reveal Weber’s heartbreak over sending her eldest son, Hanus, 8, to England (and subsequently Sweden) to protect him during the war – and, in fact, he did survive.

Weber’s letters reveal an ordinary mother living in extraordinary times. In the years leading up to World War II, Weber and her friend corresponded about miscarriages, premature and stillborn babies, breast-feeding and childhood illnesses. The letters were found accidentally in a London attic in 1976. Hanus Weber received them in 1977, but they sat unread for over a decade as he struggled with reopening the deep wounds of his childhood.

Thankfully, Hanus did find the courage to read them, and to share his mother’s words with the world.

“Dancing on a Powder Keg” provides an unparalleled window into the ways in which anti-Semitism gradually, but systematically, boxed in people like Weber. She wrote to von Lowenadler in 1939, a month before sending Hanus to London, “I have never been ashamed of the fact that I am a Jew. But now, when we are being hunted down like animals, when we are robbed of our homeland where we’ve lived decently and honorably for centuries, when the biggest and most powerful countries indeed regret our fate with indignant words, but otherwise secure their gates against ‘undesirable elements,’ today I’m carrying my Jewishness as an honor.”

“Dancing on a Powder Keg” also brings together about 60 poems that Weber wrote while in Theresienstadt from 1942 to 1944. Her husband, Willi, buried the poems and then retrieved them after the war. Here is an excerpt from “Letter to My Child”:

My dear son, it is three years today

since you traveled, all alone, far away.

I can still see you in the Prague station, on that train,

in the compartment, shy and tear-stained,

your curly-haired head leaning toward me,

how you begged, “Let me stay with you, Mommy.”

That we sent you away seemed to you cruel,

You were eight years old, small and frail,

and as we walk home without you, each step I take

is harder, it feels as if my heart will break . …

Weber’s story and words left me broken-hearted. While “Dancing on a Powder Keg” can be painful to read at times – and at points you wish you had more historical and personal context to understand some of the letters – it is certainly worthwhile.

HILARY LEVEY FRIEDMAN (hllf@brown.edu) is a sociologist who teaches in the Department of American Studies at Brown University, and a board member at Temple Torat Yisrael in East Greenwich.