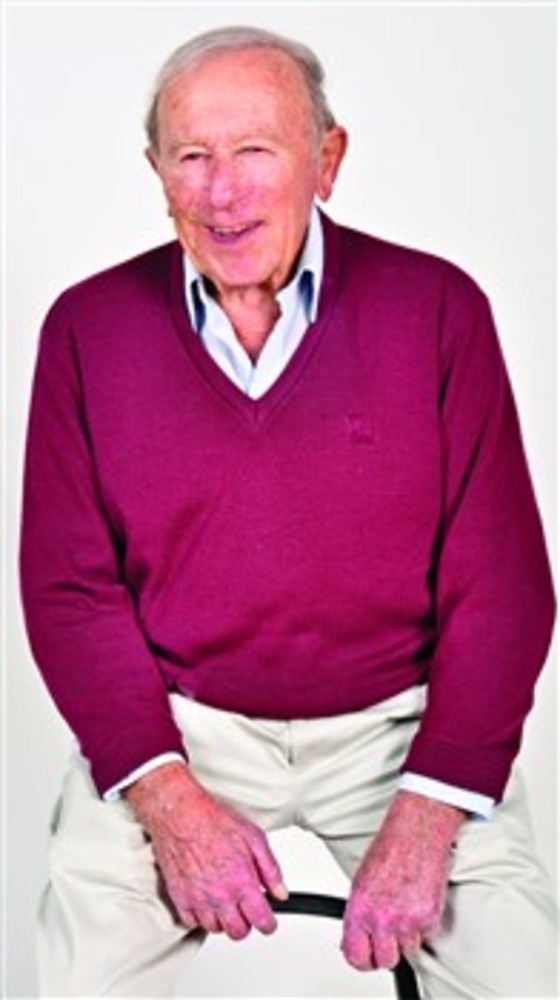

Abraham Zeltzer, a soldier of life

Abraham Zeltzer

Abraham Zeltzer

Abraham Zeltzer is 93 years old. He espouses the wisdom of old age, but many of the insights he lives by have been in his arsenal since his 20s. The unpredictability of life is a lesson he learned while serving in the U.S. Army Air Forces, where he stayed throughout WWII. In 1941, he was a student at the New England Aircraft School at Logan Airport in East Boston. As soon as the war broke out, Zeltzer enlisted, becoming a crew chief and working on fighters and bombers for four years. Once, when he was eating lunch in the mess hall, he heard a huge explosion. A B-24 airplane had caught on fire, and the fire department, unaware that the plane was loaded with bombs, arrived to extinguish it. All the men died. Looking into space, Zeltzer says, “I still remember a GI’s shoes – neatly tied and nobody in them. I think back about all these people blown to bits. You couldn’t even send anything to their families.” Later, when one of his three sons died unexpectedly of a heart attack at the age of 45, Zeltzer again experienced the helplessness and anger at the cruelty and volatility of life. He kept busy with work.

Unlike many of his generation, who held the same jobs throughout their lifetimes, Zeltzer tried various positions, the last of which, Citrus Fruit Inspector for the Florida Department of Agriculture, was a job he held in his 80s. His career history started when, at the end of the war, he found a job at Logan Airport. After flying in lobsters from Canada and Nova Scotia for a couple of years, Zeltzer applied to serve as a mechanic for the Navy’s Aircraft Overhaul Repair Base. Sixteen years later, he went to school – within the Navy – and became an instructor, teaching Israelis, Iraqis and Syrians how to test, overhaul and repair planes for the next six years.

When an opportunity presented itself, Zeltzer decided to try his hand as an entrepreneur. He and his sons bought some land and opened a garden center in Seekonk, offering planting, cutting and lawn maintenance services to businesses and residences. At one point, he says, the business had 400 customers and three crews in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Zeltzer says their chance at the American dream came to an end when a giant competitor moved in next door, forcing them to sell their landscaping company that went bankrupt a year later. Zeltzer is still upset about the predominance of enormous corporations that, he believes, monopolize business, “They do a lot of harm.”

Zeltzer’s stories confirm that much of what happens to a person in life is outside his control. After his wife, Betty died, he remarried. His second wife, Pat, a dedicated ballroom dancer, recently tripped on her oxygen tank, fell and broke her hip. Currently, she’s in a hospital in Florida, where they live, while Zeltzer is in Barrington at his son’s house, recovering from his second stroke. He talks about the handsful of pills he has to take three times a day, about the strain his ill health puts on his family, about the peace and quiet he craves. With old age comes the time to contemplate life’s choices. Zeltzer says he is no longer as observant as he used to be. Back in the day, he didn’t miss one holiday and ate only kosher meals. He wanted to carry on his dedication to Judaism in the Air Force. His first morning there, he put on his tefillin and his tallit and began to pray. After some mocking (“People thought I was a nutcase.”), he not only stopped praying, but also started eating non-kosher food since choices were scarce.

After the war, he rededicated himself to religion, becoming the treasurer of Congregation Sons of Zion, a synagogue on Orms Street in Providence, where he stayed until it merged with Congregation Beth Sholom and the property was sold to the Marriott Corp. There, Zeltzer handled the synagogue’s books and made Minyan many mornings. After services, he’d join his fellow worshippers in a modest meal of boiled potatoes, herring and a shot of whiskey.

Zeltzer also was the chairman of the Providence Hebrew Day School board. His son, Barry Zeltzer, recalls, “I used to go door to door with my father on Sunday mornings, asking for donations for the school. I can remember people closing the door on our faces, but my father never gave up and kept going until he made enough donations that day for the school.” In addition, Zeltzer often performed various custodial jobs and helped maintain the grounds.

Zeltzer reminisces about raising money with Louis Korn, Joe Dubin and Tom Perlman. He met the latter while playing handball at the South Providence YMCA. Zeltzer’s assurance to Perlman, the man Barry Zeltzer calls “a financial anchor of the school,” that his kids were very happy at the PHDS inspired Perlman to bring his own children there. The two joined forces in helping the school move. The elder Zeltzer explains that the East Side residents hesitated to donate funds out of fear that the religious school wouldn’t fit in the neighborhood.

Barry Zeltzer says, “The school was very fortunate to have my father on their board.” Now, Zeltzer’s great-grandson, Binyamin Cohen, is attending PHDS, a third-generation student following in the footsteps of Zeltzer’s daughter, Roberta Winkleman, and Zeltzer’s granddaughter, Abby Cohen. Thanks to the dedication and devotion of Zeltzer and other volunteers, many children can enjoy religious education in their neighborhood.

Editor’s Note: Several weeks after this interview was conducted, Abraham Zeltzer returned to Florida. He died on Dec. 2. His obituary appears on page 31. We are grateful to the family for encouraging us to run this interview. May his memory be a blessing.

IRINA MISSIURO is a writer and editorial consultant for The Jewish Voice.