Book empowers women to silence online trolls

There is no right way to be a woman online, just like there is no right way to be a woman in the world. No matter your preferences, your skills, your education, your style, your background, someone, somewhere, will have a problem with it. And they will let you know.

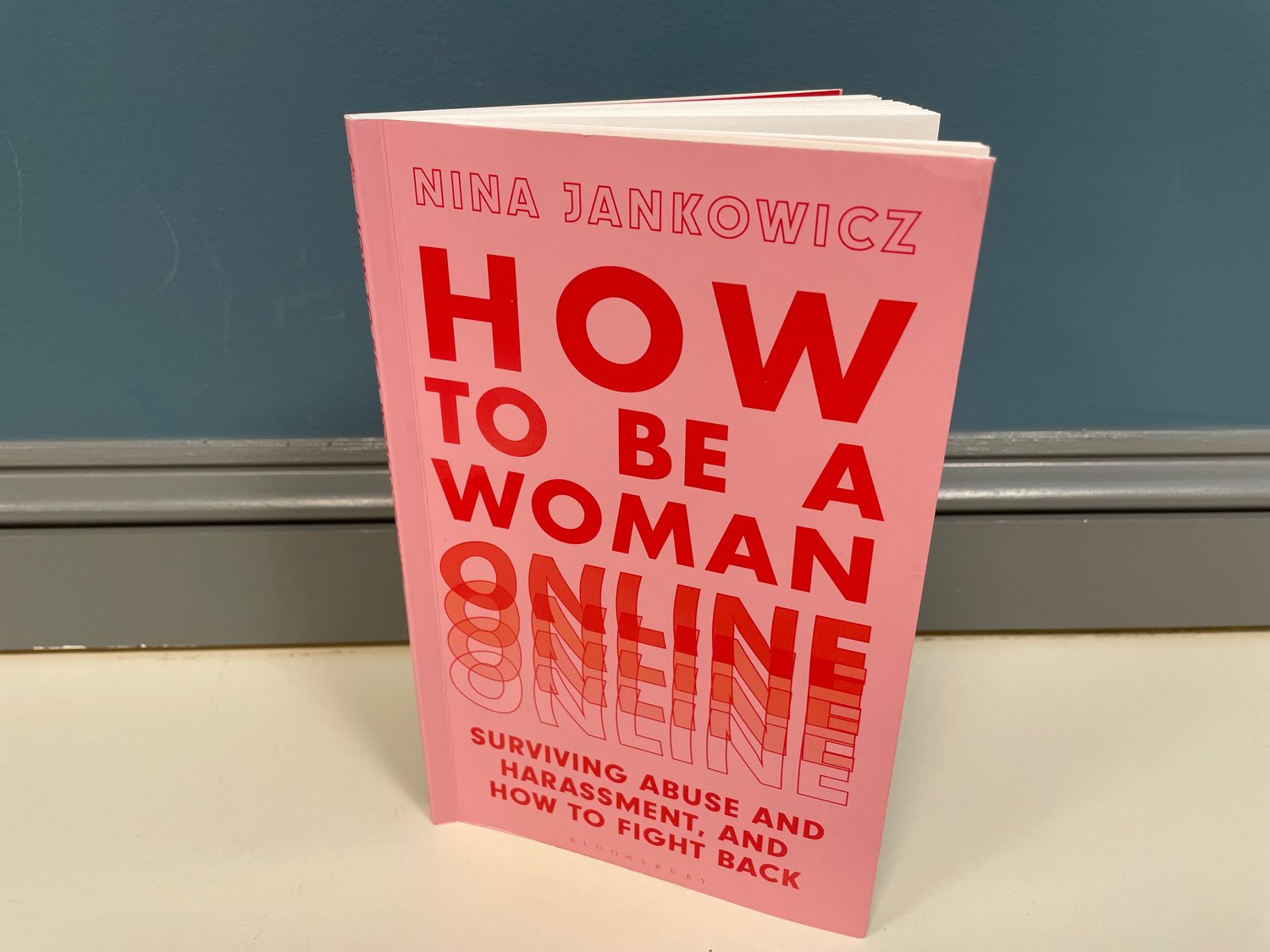

Nina Jankowicz’s “How to Be a Woman Online” (Bloomsbury Academic, 2022) is part explainer, part how-to, about how women can survive on the internet as public-facing figures.

For women who are online, the parts of the book that explain how bad the situation is will seem obvious, but they weren’t written for us.

“Employers often do not have the systems in place to support the women representing them in the public sphere,” Jankowicz writes, and the parts of the book that outline the dismal online situation are written for them.

For women online, the book has actionable steps to stay safe(ish) online, often listed at the end of chapters. In a world where law enforcement hasn’t kept up with the online sphere and where social media platforms either can’t or won’t keep up with the tactics of online trolls, safety is relative.

It is understandable that some women think, “Why even bother to participate?” However, the women in this book, and their stories, make a case for more participation in public spaces by women, not less. Cindy Otis, a former CIA officer and disinformation expert, is quoted in the book as saying, “I know I’m limiting my professional progress each time I scale back on social media.”

Being an active industry expert on social media can not only enhance your career, but it can also act as much needed counter-programming to the dominance of male voices and influence online.

One striking (and chilling) theme in the book is who the trolls are. We’re often told that internet trolls are disenfranchised men living in their mom’s basements, but they are just as often professional people coordinating the takedowns of their female colleagues and peers.

Who is at risk for an online attack? Essentially, any woman with opinions online. Van Badham, an Australian activist, playwright and columnist for The Guardian, is quoted as saying, “You may not think you’re famous, but if other people do, you’re in trouble.”

With the increasing audience segmentation of social media, you could very well have only a handful of followers but be perceived as famous. The point of some trolling is not only to silence women but for the trolls to hijack her audience and influence.

“This, they hope, will encourage you to finally shut up and make room for their infinitely more worthy thoughts,” Jankowicz writes.

Again, we must deal with the age-old idea that there is only so much air in the room, and that air is for men. Though the book walks the reader through a sampling of the sort of trolls who exist online, these examples are for outsiders – women already know them well. There’s the man who always has some reply to your every point, the guy who acts like an ally only to turn on you, the man who asks you questions he could easily Google, the older man who just knows better than you about anything you have to say, the neo-Nazis, the fascists, the Men’s Rights Activists. With the exception of the last group, these are men that most working woman have had to deal with in real life.

“Women are socialized to be accommodating, but your social media profiles are not a democracy,” Jankowicz writes. Mute the trolls, block them, deny them influence and notoriety, and move on, she writes.

Many of the women profiled in the book make it clear that you are often on your own in dealing with a coordinated attack. No one is coming to save you, so it is imperative that women online build their own networks of support and have the tools they need to fight back.

“It is a privilege to protect oneself,” Jankowicz writes.

Not only that, but with the new verification issues on Twitter, it is becoming harder than ever for marginalized people to protect themselves from imposter accounts. If the largest corporations in the world can’t protect themselves from spoof accounts, what chance does an ordinary person have?

In the chapter “Policy: Making it Work for You,” the author walks us through each major social media site and the tools they offer to deal with trolls. The U.S. legal system isn’t much use to women targeted online, so she urges women to read the terms of service and understand reporting policies for each site.

In the chapter “Community: Cultivating a Circle of Solidarity,” Jankowicz reminds us that “Social media is supposed to be social.” She urges women to weigh in on topics they’re interested in or have expertise about, to reach out to people with whom you have something in common, to make jokes and tell people their dogs are cute.

She advocates for building community with other women by following them, engaging with them, sharing content from women instead of men, amplifying other women, and calling out harassment of women when you see it online. She urges building online solidarity with women before you need it.

Jankowicz also suggests that you work with your employer to create a policy on how to deal with online harassment before it happens.

“In most cases, it will likely fall to employees to mount a campaign with an organization’s leadership to protect those who might endure online abuse,” she writes.

Jankowicz suggests spelling out the problem to your employer and asking for a new policy regarding online harassment. She gives the example of Defector Media’s Human Resource policy: “Every Defector employee has a precautionary subscription to DeleteMe, which can be upgraded to ‘white glove service’ during severe campaigns.”

Having these policies, Jankowicz writes, “builds the circumstances in which women, who often preemptively self-censor in anticipation of online abuse, can feel safer to publicly express themselves.”

For me, this is the key solution offered in the book. I know many women, myself included, have shied away from participating in social media discourse not because we didn’t have something to say, but because it seemed inevitable that whatever we said would lead to a harassment campaign.

Jankowicz will tell you that it is inevitable, but that doesn’t mean you cannot mitigate it, handle it or move past it. But it is time-consuming, expensive and difficult to do so, so ask your employer to shoulder some of the burden.

She also points out that women being silenced in the public sphere is a feedback loop that will only lead to worse things for women in the long run.

“Silence is a norm we simply cannot afford to accept,” she writes.

SARAH GREENLEAF (sgreenleaf@jewishallianceri.org) is the digital marketing specialist for the Jewish Alliance of Greater Rhode Island and writes for Jewish Rhode Island.