Cultural understanding

Krakow's 29th Jewish Cultural Festival attracts thousands of Jews and non-Jews

Prior to World War II, about one-tenth of Poland’s population was Jewish, and Jews made up almost a quarter of Krakow, Poland’s residents. By the end of the war, 90% of Poland’s Jews had been killed by the Nazis and their accomplices. Many of the Jewish structures in Kazimierz, an area that the Polish King Casimir the Great invited Jews to settle in during the 14th century, still stand in Krakow, though they remain largely emptied of Jewish occupants.

In June, I flew to Krakow for the 29th Jewish Culture Festival (JCF), 10 days of concerts, film screenings, walking tours, photo exhibits, literary programs, Torah classes, panel discussions, lectures and culinary workshops attended by thousands of people from Poland and abroad.

The JCF’s founders, organizers and attendees are mostly non-Jewish Poles. The more people I met in Krakow and the more of the festival I experienced, the more I wanted to understand why so many non-Jews seemed invested in learning about and promoting Jewish culture.

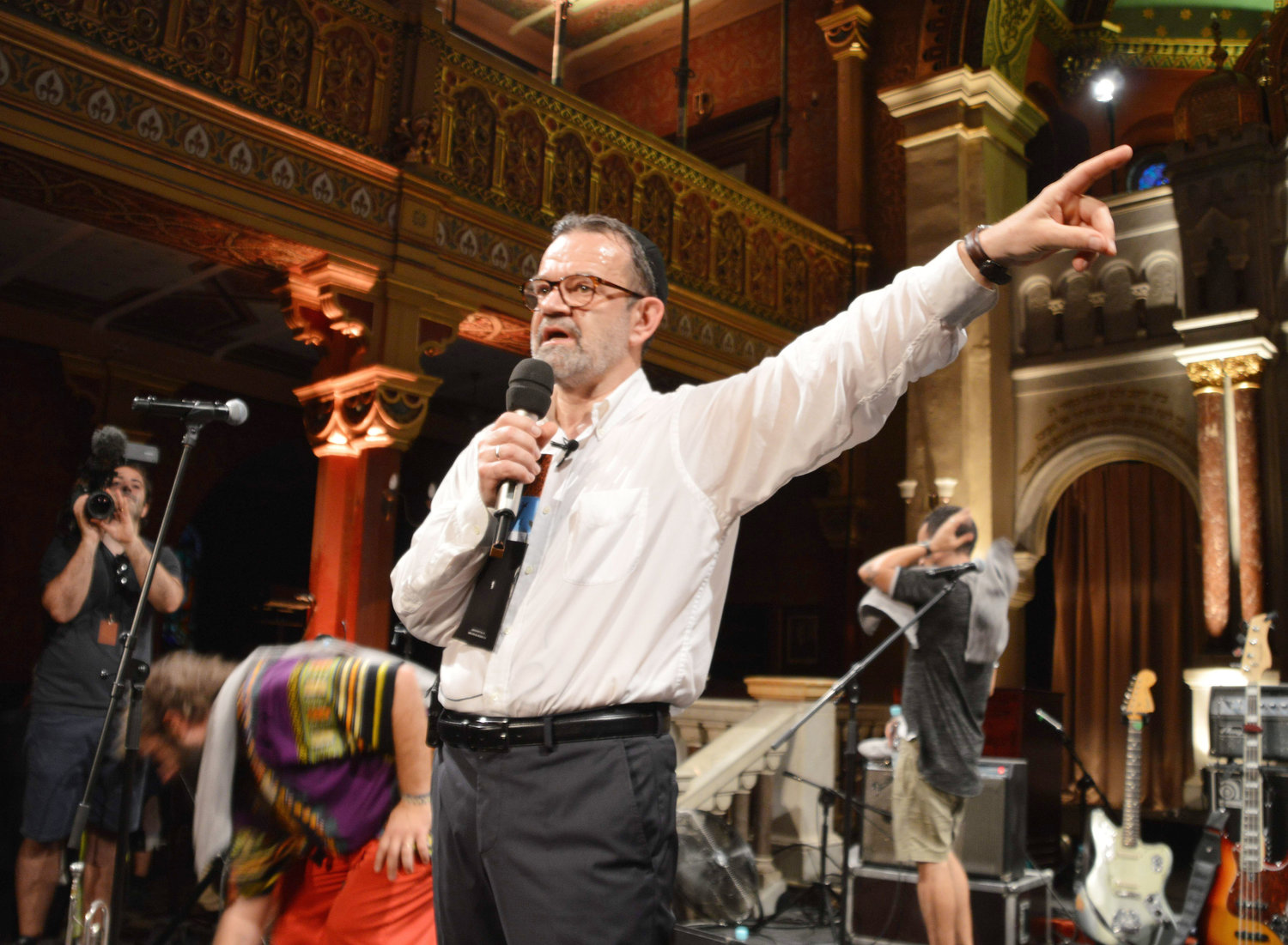

"It is very difficult to answer, ‘Why are you doing this?’ It is like answering, ‘Why do you breathe and live?’ I am a man who is aware he was born in the largest Jewish cemetery in the world, but also that six years of Shoah [the Holocaust] cannot eclipse a thousand years,” Janusz Makuch, the festival’s non-Jewish founder and director, told me when we sat to talk in Cheder – a Middle Eastern-themed café and meeting place situated in a former Jewish prayer house – about his decades of work on the JCF.

“When I started putting together a Jewish festival at age 28, I was the only one in Poland. Now there are over 40 Jewish culture festivals. I felt the obligation to plant the seed. It came from a deep responsibility to memory, but also from deep fascination with and love of Jewish culture,” Makuch said.

“When I started to plant the seed, I noticed that many [Polish] people – especially, but not only, young people – long to learn, each for their own reasons, about Jewish culture, which is also a part of their culture. Come on! We were living a thousand years with Jewish people on the same soil, as neighbors!”

The first festival event I attended at the Galicia Jewish Museum was a guided tour through Chuck Fishman’s photography exhibit, “Regeneration: Jewish Life in Poland.” After the tour, museum educator Anna Wencel and I talked about her interest in Judaism from a young age and about her work at the museum since 2008.

“When I was 8 (in 1989), I by chance went into a local Jewish cemetery with a friend. We saw tombstones, but we could not read the inscriptions. We saw one tombstone with a crown and thought maybe it was the grave of a king or queen. It seemed like something from a fairy tale,” Wencel said. “I told my grandmother what my friend and I found, and she explained to me that it was a Jewish cemetery.

“My grandmother was born in 1923. She refused to tell me anything about the war – it was too traumatic for her – but she talked a lot about the interwar period [between World War I and II], as if everything was better before the war.”

Though Wencel loves her education work, she said being a non-Jewish guide at a Jewish museum has its tensions.

“At the museum, I often get asked if I am Jewish by Jewish people, implying that it is not my story to tell. And some Christians ask the same thing with suspicion, implying a non-Jewish person cannot have actual knowledge in this field – ‘How can you know this?’ Sometimes it gets a little bit anti-Semitic with non-Jewish visitors, implying that they want to listen to ‘a real Jew,’ someone representing this ‘exotic’ culture,” Wencel said.

But, she added, “There are people for whom their job is their passion. I am in that group. I do not believe in dividing things into ‘this is my story; this is their story.’ At the end of the day, we are all human.”

The next event I attended at the museum was a talk by Paul Schneller, a Swiss veterinarian specializing in exotic animals who is also a professional photographer. In “About Polish Jews: See You Next Year in Krakow,” he discussed his family’s taboo surrounding his Jewish great-grandfather, Saul Chaim Grunfest, who was a communist, a friend of Lenin and the first Jewish Social Democratic Party member in Switzerland. Neither Grunfest’s communism nor his Jewishness were spoken of in Schneller’s home, though it was clear from his name that he was Jewish.

Schneller and I met for a drink the next day. “I am very attached to Krakow and Poland, but Krakow is not representative of Poland,” he said. “It is an unusual place. When you first come to Krakow, you just see the tourism here, but there is something more and deeper here about Jewish life than the superficial tourism. The tourism itself is superficial, but it allows for a conversation to take place, like we are having now.”

Schneller continued, “There are more non-Jews active here in Jewish life than Jews. The Jewish Culture Festival is run by non-Jews. The director of the Galicia Jewish Museum is not Jewish. This Jewish life here would not exist without the non-Jewish people. When I ask Polish people about this activity, they say, ‘I feel a gap. I feel there is something missing. We have to fill this gap.’

“Jewish absence in Poland has been described as a phantom limb. My interpretation is that with their interest in Jews, Polish people are involved in healing. It is a possible therapy – probably not conscious, but subconscious – to deal with a phantom pain, the trauma of the Nazis.

“They miss the Jews. They had a thousand-year history living alongside the Jews, and in six years, the Nazis wiped it out.”

Jakub Nowakowski, 36, has been heading the Galicia Jewish Museum since 2010.

“If you go to the small towns, about which there are not media reports, you also see that many of them are interested in Jewish culture and history, and organize Jewish festivals as well. If you go to the small villages that have these festivals, there is no money made there. It costs them money,” he said.

“Why are people in these remote areas spending money to renovate synagogues and have Jewish festivals? Why do teachers come here? Why do they come to spend their vacations studying in Krakow? They are not doing it for money.

“Is it because we feel guilty? Of course some Poles feel guilty for what was done to the Jews. Others just miss the Jews, who are still alive in the memories of their parents and grandparents. But there is also the pride of coming from a multicultural world that was here. People look around, see homogeneity, and look for something different.

“It is about memory. It is about finding peace and moving forward. We live in the post-Holocaust space in a way no other country does. Traces of Jewish life and death exist so close to each other.”

During my visit, I got to know several of the festival volunteers, called machers, including best friends 25-year-old Joanna Chojnacka and 26-year-old Dominika Kołodziej. They met me for lunch one day at Hevre, a former beth midrash (study hall) owned by the Gmina Żydowska, Krakow’s official religious Jewish community, and now leased as a restaurant and bar. Hebrew calligraphy and paintings of holy places in Israel still adorn its walls.

Kołodziej is completing a master’s degree in Jewish Studies at Krakow’s Jagiellonian University.

“I always had an interest in Jewish history, but more of the interwar period, because I felt it was not studied much,” she said. “I was especially interested in the music and the movies of the interwar period – many of which were made by Jews, especially in Warsaw. I always liked hearing songs in Yiddish. Warsaw has a specific dialect, and most of it is from before the war. Many of the words are in Yiddish.”

She continued, “It has become more and more normal to see Jewish people here. There is curiosity, maybe from tourists, but in Krakow, people know there are Jewish people here, and they fit in the area and no one is surprised anymore. I feel it is very specific to Krakow. We are used to seeing Orthodox people rushing to synagogue for Friday night. It is natural for us now.”

Chojnacka, who also majored in Jewish Studies, recently finished a soon-to-be-published novel, “Szpagat” (an insult in Varsavian dialect for someone well-educated), about a Jewish tailor who returns to Warsaw after the war and finds that the Jewish quarter is gone.

“I had this idea four years ago. One of the reasons I chose Jewish Studies was to learn about Jewish life and to learn some Yiddish. I wanted my writing to be as authentic as possible. It is impossible, but I said, ‘I will try.’ At the time, I did not tell my professors why I wanted Jewish Studies, because it is quite unusual that you write about something that does not belong to you.

“I cannot consider myself Jewish, and I am writing from the perspective of the main character, who is a Jew. I was worried people would say, ‘It is not your thing. You should not write it.’ But then I started saying to myself, ‘Then who will write it?’ I wanted to tell the story of the Jewish people of my city, who are also my people.”

As for why Poles are so interested in Jewish culture, Chojnacka suggested, “I think Polish people still miss Jewish culture. We were neighbors. We were very close. More and more we miss it. People want to feel it, but it is very hard to feel it authentically. We are still searching for the way to show it.

“In Krakow, we still have the buildings and the synagogues, so it is easier. There is a Jewish quarter. I feel the Jewish Culture Festival is doing this very well. It is a very good way to show people Jewish culture – modern Jewish culture and with a focus on Israel. We are searching for something Jewish in Poland and this is the way to learn something authentic.”

Indeed, the JCF, with its many and varied offerings, does an excellent job of presenting contemporary Jewish culture and of grappling with current Jewish issues in Poland. While there were events in Polish and in English, many of the speakers, authors, cantors, singers, musicians, artists and religious figures participating in the festival were Israeli, which was no accident.

“Most importantly, I know that Israel is the center of Jewish life,” Makuch, the JCF’s founder and director, told me. “It is a festival dedicated to contemporary Jewish culture and life, which is centered in Israel. Israel is also a center of my life. Being Jewish, you are connected to Israel. Israel is my country and chosen land too.”

SHAI AFSAI lives in Providence. In November he will be presenting a program with Salve Regina University’s Dr. Sean O’Callaghan and Dr. John Quinn on “Newport’s Irish-Jewish Rabbi, Theodore Lewis, and Dublin’s Jewish Community” as part of the Museum of Newport Irish History’s lecture series.