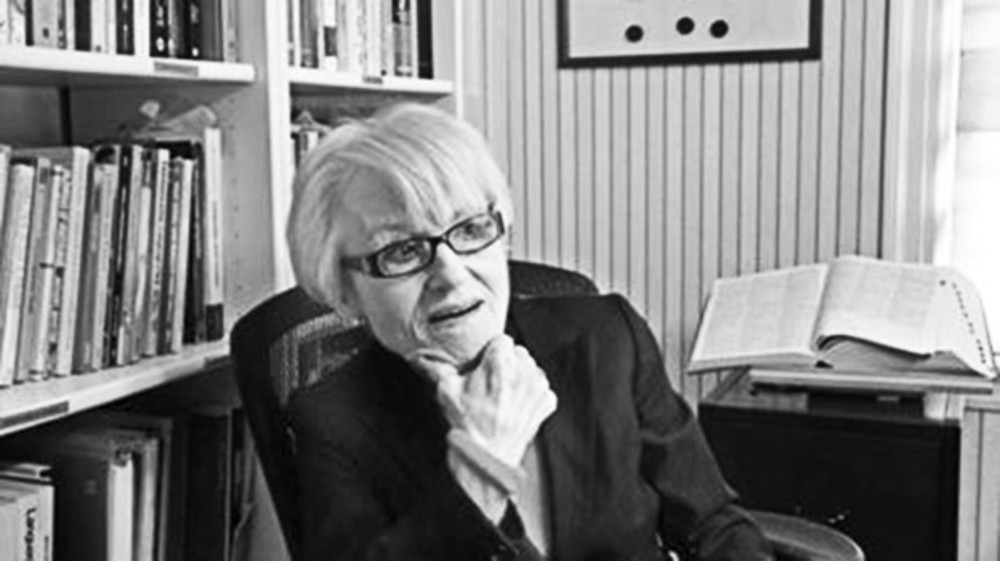

Elaine Chaika: teacher, author, humanitarian

This native Rhode Islander is anything but shy

Among Elaine Chaika’s quotes on the site Goodreads is one by Elie Wiesel. “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of art is not ugliness, it’s indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference.” This professor emerita of linguistics from Providence College is not indifferent. Her work is motivated by her desire to know how people understand. Chaika doesn’t shy away from any topic; in fact, she did a study in the schizophrenic ward of Butler Hospital to write a book on psychotic speech. When she sees something that she doesn’t agree with, she rebels. In her childhood, she jumped on the backs of bullies who called her names. During graduate school, she marched against the Vietnam War. Now, in her retirement, she is giving voice to dogs in her new book, “Humans, Dogs and Civilization.”

Chaika is a whisper of a woman. Despite her petite figure, she commands an imposing stature. Chaika continues her role as a wordsmith – that word is her site’s (elainechaika.com) tagline, as well as a part of her email address. I’m quickly reminded that Chaika doesn’t do anything halfway. If she’s teaching grammar (I was in her class in the ’90s), she creates the most colorful illustrations to explain the difference between “lie” and “lay.” If she’s eloping with a new husband, she goes to the wilderness. If she’s making tea, she brews it from scratch.

When I see her again after all these years, she doesn’t pretend to remember me, despite having been my professor for two classes. Instead, she asks, “Are you Irina?” as she approaches in sky-high wedges. Her longish fingernails, painted in sparkly blue polish, click against the china. I find a couple of chains in one of the cups; she explains that they belong to one of the antique dolls that share the apartment with Chaika and her husband Bill.

False modesty is an unknown concept to her. Chaika has no qualms about praising her six books, disclosing how much her out-of-print book goes for (upward of $200), quoting complimentary introductions of herself at conferences, reciting her accomplishments (“Of my cohort, I’m the one who published the most articles and chapters in books”) or regaling the listener with tales of romantic adventures worthy of a Lifetime movie.

I learn about her disillusionment with studying philosophy at Pembroke College; “It was just boring.” She had a better time waiting tables in Maine, where she met her first husband, a “gorgeous geologist” who hired a Presbyterian minister to marry them on their way to a remote cabin in the woods. It wasn’t until she had a baby in 1955 that she hesitated to live in a place with no sign of human habitation. Yet, when her parents pressured the young family to return to Rhode Island, she heeded their reasoning.

Five years later, Chaika was married to Bill – a Jewish man whom her family found more suitable. She shares that she loved growing up in a religious household, where everyone spoke Yiddish and kept kosher. “I value my Orthodox upbringing,” Chaika says, naming charity and compassion for animals as some of the virtues that appeal to her.

Animals are sacred to her. In fact, in addition to her upcoming book and one of her blogs, “Dogs and Wolves,” Chaika has a Facebook page called “Amazing Dogs – Yours and Mine” and a Twitter account @OurAmazingDogs. Chaika reveals that, without dogs, humans wouldn’t have developed civilization. She says we would still be hunters and gatherers had it not been for these herders that help humans to get animals into flocks. She tells a story to illustrate.

Chaika is in the British Isles on vacation. She and Bill are watching a herd, as a shepherd, accompanied by his dog – a black-and-white border collie, – is walking along the meadows. As the sheep graze, the dog ensures order. All of a sudden, Chaika is having a flashback. It’s 1937. During a game of tag, she accidentally rips a girl’s belt. After school, a gang of tall, strong girls is waiting for her. She begins to run. Flippy, her beloved dog that meets her every day at 3:30, gets the pursuers into formation and keeps them there, preventing anyone from being able to reach out and grab her. “He saved my life,” Chaika says.

Her love of dogs has never wavered. A self-described “glutton for research,” Chaika is fascinated by the way animals communicate without words. She believes that language is not the first step in encoding thoughts, actions or feelings. Chaika analyzed her dogs’ train of thought and behavior, noting that their way of thinking was not language-dependent. Therefore, she found, to act morally, one doesn’t have to be able to discuss the conduct, as most philosophers claim. She is adamant that animals are much more than just a bundle of responses to stimuli.

As someone who makes conclusions through careful examination, Chaika reveals that her favorite part of teaching involved observing students, hearing their insights and considering their arguments. I tell her that I still associate her with “Do the Right Thing,” a film she used in her class. It’s fitting that our interview occurs on the film’s 25th anniversary. Chaika raves about the movie, saying it was “synthesized to perfection.” The two quotes at the end – the one that deems violence as society’s destructive force and the other that credits violence as an intelligent tactic when used in self-defense – must resonate with Chaika, who marched for peace in the ’70s, watched her parents suffer the effects of anti-Semitism, listened to her grandmother’s stories of Ukrainian pogroms and lost 200 family members in Babi Yar. At the moment, she’s attempting to do the right thing for dogs – animals that deserve to be recognized as thinking creatures.