Greater focus on the victim is key to repentance and repair

In the past few years, we have had an endless stream of public apologies for bad behavior. Some seem genuine, some were clearly written by publicists, some accept responsibility, some deflect blame. The apologies have come from comedians, institutions, government officials, local coffee shop owners. So many people have said they are sorry, but it often feels like very little has changed. So many people have continued to do the same things they were so sorry for a year ago.

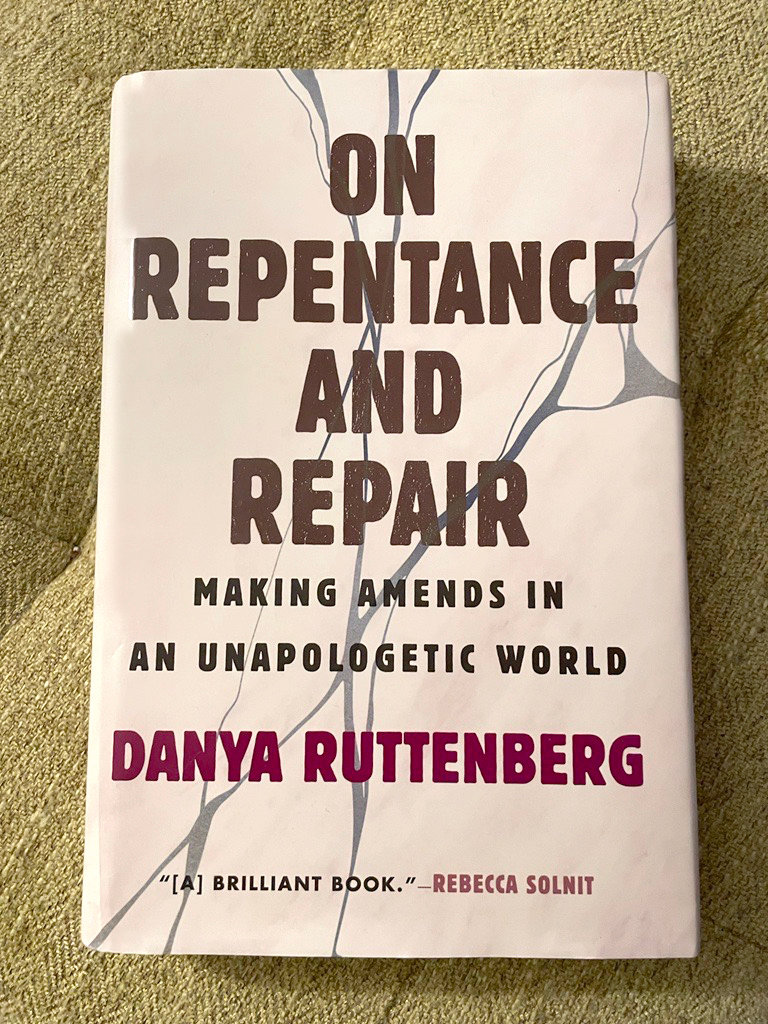

This cycle happens when people and institutions are doing the public part, the apology, without ever doing the hard work that needs to be done. In “On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World,” (Beacon Press, 2022) Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg uses the framework laid out in Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah to explore how we can all do the work of healing the many fissures in our society and our lives.

To do the work of repentance and repair, people who have caused harm must decenter their own feelings and desires, and focus on what the victim needs. Rabbi Ruttenberg writes, “This is another common pitfall in repentance — not worrying enough about the person who has been hurt and too much about ourselves and our own desire to assuage our conscience or protect our reputation.” This is why so many apologies ring false; they are clearly there to manage a reputation. So few apologies include an acknowledgment of the harm that was done, a necessary part of Maimonides’ framework. To repent you must first tell the truth.

Ruttenberg is careful to point out that accountability and punishment are not the same. Through numerous examples, she shows the many ways our American justice system can get in the way of victims getting what they need — an acknowledgment of the harm caused to them.

“Of course, the critical role of confession is in its potential to liberate victims of great harm — it marks an end to the denial of their experience and an affirmation of the legitimacy of their suffering,” writes Rabbi Ruttenberg. The same is true for many large institutions, from universities to your place of work.

When harm is caused by an institution, the priority is often protection from legal consequences. Victims are told that the harm they suffered wasn’t real or grave enough in an effort to maintain the status quo. It happens when an HR representative tells you that your report of harassment will ruin a man’s career when what you want is to never be alone in a room with him. It happens when an institution shies away from punishing wrongdoers instead of helping victims.

“In a victim-centered approach, the question is not, ‘What are the things harmdoers must do so that an institutional ecosystem that depends on them can return to normal?’ Rather, it asks: ‘What do victims need, and are they getting those things?’ ” asks Rabbi Ruttenberg. The focus, then, is not on punishing the perpetrator for the sake of punishment. The goal should be to change the very structure of the institution so the victim can feel and be safe.

The book continues, “As the psychologist Paul Mattiuzzi notes, attempting to rely on an institution for support carries inherent risks. Filing a complaint carries the risk that you will be doubted, blamed, refused help and denied protection. People take the risk because they trust the institution to ‘fix it and make it right.’ When that trust is violated, the hurt can cut deep.” So many people have felt this hurt and have not known where to turn because the truth is, many organizations and people are more worried about looking good than doing good.

There is a tendency in our society to obsess over “what is in people’s hearts” when they behave badly. If they said something antisemitic, are they an antisemite? If they did something sexist, are they a misogynist? The fight over labeling people can miss the point — all we can judge people on are their actions. There is no way to truly know what is inside another person’s mind. “Being someone who caused harm is not a fixed identity – or at least it does not have to be,” Rabbi Ruttenberg points out.

To do the work of repentance is to change, to let go of “the story of ourselves as the hero” and write another story of redemption and transformation. “Maimonides teaches that perfect repentance is arriving at the place of harm and making different choices,” the book tells us. Perfect repentance is becoming a different person, one who does not cause harm.

What is the role of forgiveness in all of this? Ruttenberg points out that repentance and forgiveness are both acts that can be done outside of the relationship between perpetrator and victim. Indeed, it may often be inappropriate for the perpetrator to be in contact with the victim as it would cause that person more harm.

To repent is not to be forgiven. That is not the purpose of repentance as it still centers the perpetrator’s desires. Pressuring victims to forgive is simply asking that the problem go away. “So often, pressure to forgive comes with a minimizing of the harm caused, a refusal to see its full impact,” she writes.

Ruttenberg does a lovely job of parsing out the many terms we tend to conflate with forgiveness. She writes: “It’s not about being willing to return the relationship to what it had been before the harm, and it’s not even about returning to any kind of relationship. Once again, that would be reconciliation, a whole other ball of wax.” A whole other ball of wax, and not the goal of repentance to begin with.

Victims, perpetrators and allies can all use this framework. For victims, the responsibility is in naming the harm. “If someone harms you, you must tell them, so that you don’t nurse the grudge or feel consumed by resentment,” the book states.

For allies the responsibility is to support the healing of the victim and the perpetrator, “The victim’s job is to take care of their own spiritual health; the ally’s job is to get into the trenches with the perpetrator,” the book continues.

A quote from Rabbi Ruti Reagan in the book puts it perfectly, “We can believe that offenders deserve support without making their victims responsible for providing it.’ ”

Being a good person is not about never causing harm, it is about repairing the harm you cause in a way that centers the needs of the person you’ve hurt. It is not about your desire to feel like a good person again.

There is so much harm that comes when people try to protect their idea of themselves, or their company, or their country as people or groups who would never hurt anyone.

If you are already good, what need do you have to become different? If you are already good, what you did must not have been so bad. If you are already good, perhaps the victim is the one in the wrong. If you are already good, who are you when that isn’t true?

Release your need to be good so that you may actually do good. “On Repentance and Repair” is just the book to help you get there.

SARAH GREENLEAF (sgreenleaf@jewishallianceri.org) is the digital marketing specialist for the Jewish Alliance of Greater Rhode Island and writes for Jewish Rhode Island.