New book suggests eating Jewishly involves improvisation

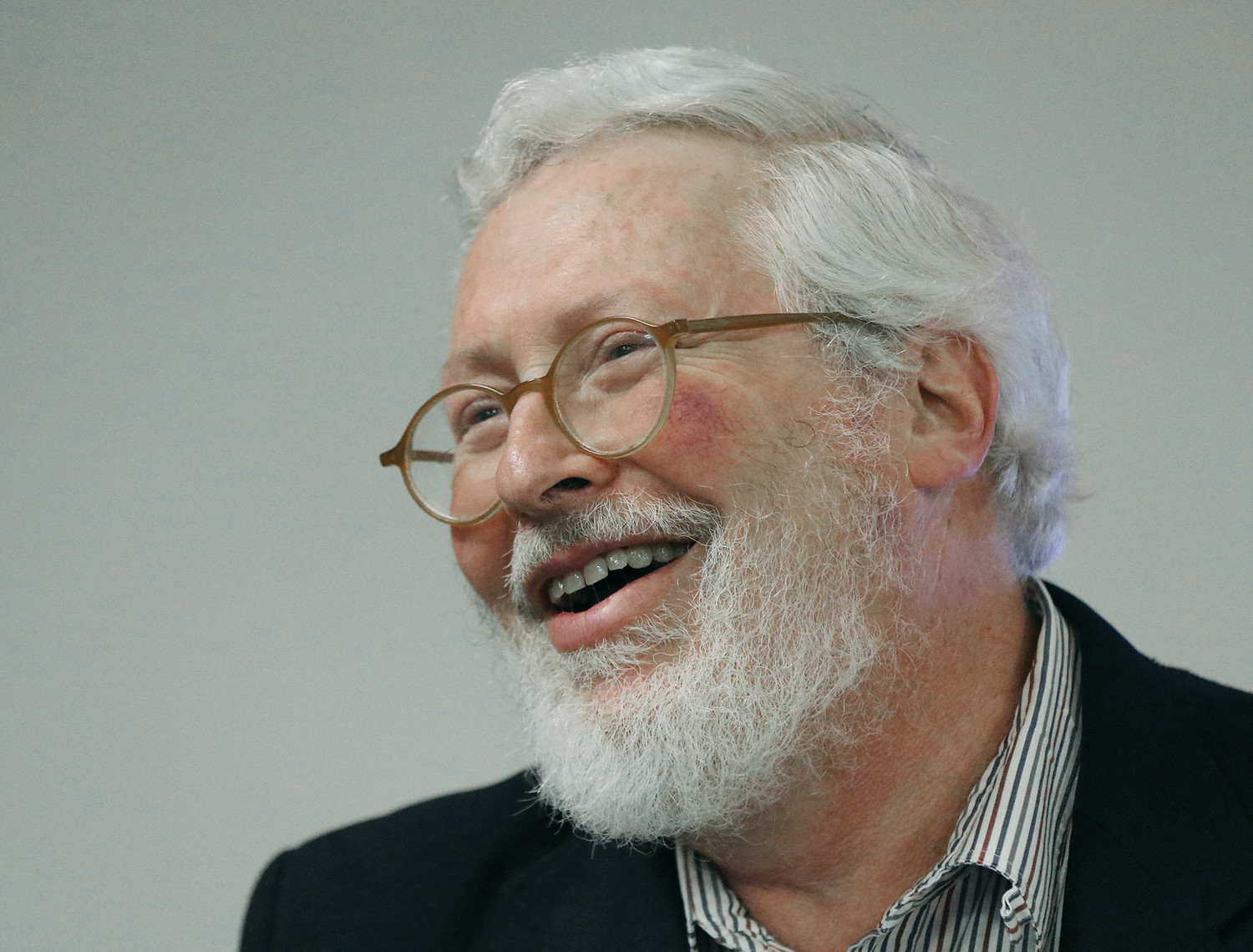

Rabbi Jonathan Brumberg-Kraus, a professor of religion at Wheaton College and the author of “Gastronomic Judaism as Culinary Midrash,” has confessed to eating possibly non-Kosher chicken.

Before you gasp, though, hear him out. He strayed from his adherence to kashrut not only in the name of exploration, but also in the interest of communal peace — thus inadvertently proving his thesis that context, not the food, is what makes eating Jewish.

During a culinary tour led by Abbie Rosner, a food writer who lives in the Galilee, in northern Israel, Brumberg-Kraus was among those invited to visit the home of Balkis Khateeb, a Nazareth woman, to cook together. Before going, Brumberg-Kraus, his wife Maya, and other Jewish women in their group shopped for food in an Arab spice store, enjoyed the aroma of freshly ground bulgur, and picked up pancakes from a bakery to break the Ramadan fast.

At the woman’s house, they learned how to cook stuffed grape leaves, use a mold to make bread, and bake cheese pastries.

And then, even though Brumberg-Kraus and his wife always eat vegetarian when they’re out, they indulged in a soup that was made with chicken stock. He explains, “I wasn’t sure she used a Kosher chicken. I figured, if not, it was halal, since she was an observant Muslim. I had to make a choice. I’m Kosher, but flexible in certain situations where it makes sense to be open communally. A lot of Jewish eating is making choices.”

The rabbi says, “I still made a Jewish choice even though I didn’t eat Kosher. Kosher is not the only way to assert Jewish identity.”

With his newly published book, the rabbi wanted to convey the idea that “there’s more than one way to eat Jewishly,” not only in the text of the book, but also in its title. Brumberg-Kraus intends to show that Jewish character can be expressed via means other than eating bagels, lox and brisket.

“The Jewish identity is always changing,” he says, emphasizing that we reinterpret old traditions and adapt new ones that are relevant to our time.

However, while the way Jews eat might have changed, the fact that “food is super important to Jewish identity” has not, the author asserts. Our Jewishness has always been rooted in food. Brumberg-Kraus points out that the book of Leviticus contains recipes that tell us how to serve God — what type of meat and wine to place on the altar. He adds that our most important holidays are celebrated by eating specific foods.

For instance, the dishes we eat during the Passover seder, such as matzah, come from rabbinic literature. But while haroset is still on our seder plates today, the ingredients in it often vary. Brumberg-Kraus points out that the Ashkenazi version contains apples and nuts, while the Moroccan one is made with dates and figs. Similarly, during Hanukkah, Ashkenazi Jews eat latkes, while Israelis often eat sufganiyot (fried jelly donuts). Italian Jews go a different route altogether, frying a breaded chicken instead.

Through stories about distinctive food experiences, the 220-page “Gastronomic Judaism” (Lexington Books, 2019) illustrates the maxim “we are what we eat” and shows how we, as Jews, connect with our roots through our culinary choices.

“We don’t all do it in the same way,” says the author. By assigning Jewish meaning to foods for rituals, holidays and ceremonies, we transform them from ordinary dishes and ingredients into culturally significant ones.

Brumberg-Kraus grew up in a Reform family that expressed Judaism by keeping Kosher for Passover — the one time when most Jews adhere to the dietary laws, he says. He still approves of this open-minded approach to religion, saying, “Jews are dynamic people. We don’t do anything 100 percent of the time.”

In celebrating only certain holidays or following only some rules, Jews are accentuating their behavior to connect to their culture, he believes.

Brumberg-Kraus’ observation that people’s feelings about food are mostly ambivalent inspired him to focus on the positive aspects of cuisine, looking at it from a religious perspective. He seeks to demonstrate that eating could be “a powerful spiritual experience that brings us together with other people and makes us happy.”

After all, we have so many identities — religion, gender, sexual preference, color, geographic location, etc. No aspect needs to be denied.

“Identity is situational,” Brumberg-Kraus says. When we choose to celebrate Halloween, we do so to connect with other people. Or when gentiles attend a Tu b’Shevat seder, they’re not just eating fruits and saying Bible passages — they’re participating in our religion to relate to us.

Brumberg-Kraus believes that when eating is done in a cultural setting, the meaning of the meal is enhanced and the pleasure we derive from it is greater. For instance, compare eating bread while browsing through social media to eating bread while celebrating Shabbat. He feels that it’s the occasion that makes the food rewarding, sustaining and uplifting. In other words, context is everything.

The rabbi is pleased that people now have a more flexible understanding of what Jewish food is. For example, when Jews go out for Chinese food on Christmas Eve, they are participating in a new tradition. Or when his family is visiting Austin, Texas, where it’s hard to find a good Chinese restaurant, they go to an Indian one; they modify the new tradition and construct their own one to adapt to the circumstances.

Brumberg-Kraus says that such eating can still be a deeply meaningful experience. As long as our “worship through the body” (the Hasidic concept of Avodah Be’gashmiut) allows us to connect with the natural world and be spiritual, it’s not a lesser form of religious practice.

So the next time you’re craving some rugelach at midnight, don’t tiptoe. Instead, wake up your spouse and make it a meaningful, communal occasion.

IRINA HAWKINS is a writer who lives in Providence.