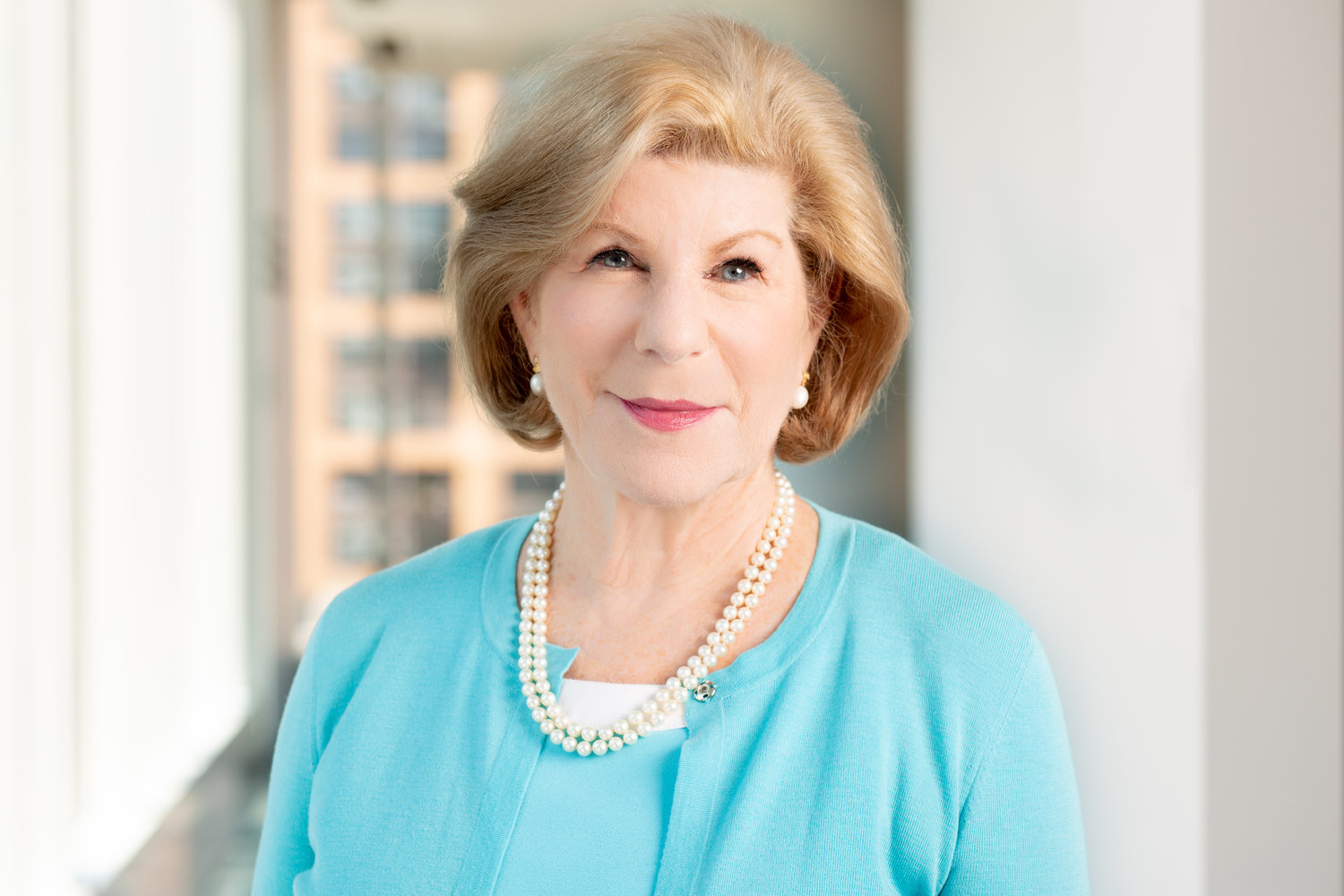

Nina Totenberg's new book tells powerful tale of friendship

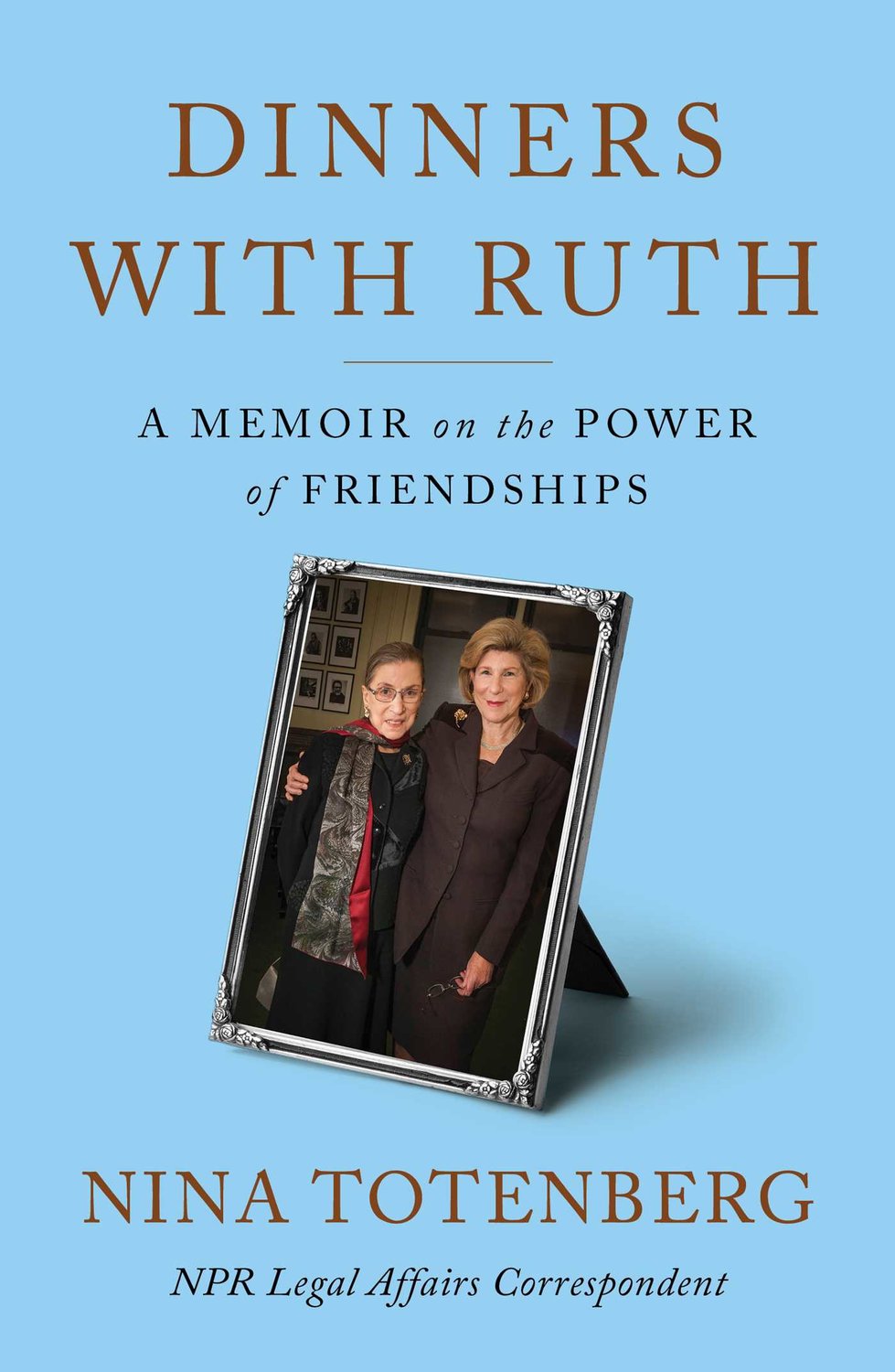

“Dinners with Ruth” (Simon & Schuster, Sept. 13, 2022) charts an extraordinary friendship between two impressive women. Though the outline of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s life is well known, there is much to learn about the life of Nina Totenberg, 78. Her father was a famous violinist, her mother a Brown University-educated woman who knew Eleanor Roosevelt and Totenberg herself a college dropout who started out as a reporter in Boston.

Though Ruth Bader Ginsburg is featured prominently in this book, the subtitle “A Memoir on the Power of Friendships” is a better example of what you’ll get from this read. Totenberg charts her friendships with the women at NPR (National Public Radio), with her two husbands, the people who showed up when her first husband was dying and her friendships with Supreme Court justices in addition to Ginsburg. There is even a chapter on her father’s “long lost friend,” a stolen Stradivarius violin.

In some ways the conceit of the book overshadows where it really shines, which is in Totenberg’s recollections of her working life. The book follows Nina Totenberg’s rise to NPR correspondent and her many years of often being the only woman in the newsroom. She details the ways in which she navigated a new working world for women and a young news organization in the early days at NPR, including getting into scrapes with the Justice Department over briefing policies, breaking the Anita Hill story and being yelled at by Sen. Alan Simpson, and working with NPR colleagues Cokie Roberts and Linda Wertheimer.

Both children of Jewish immigrants, Ginsburg and Totenberg were born about a decade apart but grew up in radically different worlds. Ginsburg’s father struggled to sell furs during the depression, and her mother worked in the garment industry. Totenberg never experienced rationing, but her father worked to free his cousin from behind the Iron Curtain. Both women were touched by the larger forces of politics and war, and both pursued careers that aimed to make sense and order out of a chaotic world.

Neither woman was taken seriously during her early career. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, despite graduating tied for first in her class at Columbia Law School, found it almost impossible to find a job. The professor in charge of securing clerkships for the law students promised that if she didn’t work out, he had a man on standby who could take over. Totenberg writes, “As Ruth put it, ‘That was the carrot. There was also a stick. And the stick was if you don’t give her a chance, I will never recommend another Columbia law student to you.’ ”

Totenberg often used underestimation to her advantage. “I broke a lot of stories because I was sassy, I was good at what I did, and prominent men, often to their peril, did not take me seriously. With their guard down because I was ‘just a girl,’ they answered my questions a bit more honestly, and my reporting often made news.”

The two women’s careers and lives collided in 1971. Totenberg had staked a claim for herself reporting on the Supreme Court. At that time, it wasn’t considered important enough to warrant a full-time reporter. “But I realized fairly quickly that covering the Court was something I could do that other people weren’t as interested in at the time. So I could carve out a small piece of territory for myself,” Totenberg writes.

As she read the brief for the case Reed v. Reed, she saw something remarkable, an argument that the law was unconstitutional because it discriminated on the basis of sex. The brief argued that the 14th Amendment’s guarantee “of equal protection under the law” applied to women. When Totenberg flipped to the front of the brief, she saw it had been authored by a law professor at Rutgers University named Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Her telephone number was listed, so Totenberg called.

After that first conversation, Totenberg called Ginsburg often to ask her questions about the law. “Her explanations were very clear, her answers were always concise and to the point, also a rarity, although I did find that lawyers and even judges were more willing to explain things to me than people in the political world were. And their explanations were often better.”

One of the more surprising parts of this book, especially for those who came up in the era of objectivity, is just how close Totenberg was to her subjects. She would host the Supreme Court Justices for dinner long before Ruth Bader Ginsburg was appointed. The line between source and friend can be a blurry one though Totenberg is quick to point out in the book, “there’s another facet of these relationships, on all sides, that no one should confuse: objectivity and fairness are not the same thing. Nobody is purely objective. It is not possible.”

Totenberg and Ginsburg became good friends. Totenberg broke large stories like the Anita Hill accusations against Clarence Thomas, and Ginsberg was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. When Ruth Bader Ginsburg was appointed to the Supreme Court, she joined Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and doubled the number of women. Though the two justices held differing political views, they still worked as a team to get their ideas heard. When Ginsburg became the only woman on the Supreme Court, she experienced something almost every woman working today has – her comments would go unheeded until repeated by a male colleague, at which time they would become “a good idea.”

Totenberg writes, “The day-to-day dismissal of a smart woman’s voice – which so many women have experienced – happened even on the Supreme Court. But it never happened when both Sandra and Ruth were seated at the table. Despite being very different people, they really were a team.”

The role of women in one another’s professional lives is the true focus of this book and where it really shines.

It is discouraging in many ways to read about these early female pioneers in their fields and realize how little has changed for many women. Indeed, there are numerous instances in which things seem to have gone backward for women. Totenberg points out in the book that in 1993, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell voted to confirm Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the Supreme Court. When RBG died in September 2020, McConnell refused a request to allow Ginsburg’s body to lie in state in the Capitol Rotunda. He did not pay his respects.

Totenberg and Ginsburg both climbed to the top of their fields. “Dinners With Ruth” makes the case that professional friendships between women are a large part of what made these careers possible. Totenberg refers to this as “the Old Girls Network” and points out that many women who worked during that era were the only women in their departments or at their workplaces. They turned to other professional women for advice, help and understanding.

Sometimes the world of work and the world of friendship are at odds, especially when Totenberg’s job was to report on the health issues of her friend. Would she spring into reporter mode, or would she show up as a friend? “At different moments in life, there are choices of lasting consequence. And I had one of those before me. For the next eighteen months, I chose friendship. It was the best choice I ever made.”

SARAH GREENLEAF(sgreenleaf@jewishallianceri.org) is the digital marketing specialist for the Jewish Alliance of Greater Rhode Island and writes for Jewish Rhode Island.