Opinion: Here’s why I’m sticking to the basics on my seder plate.

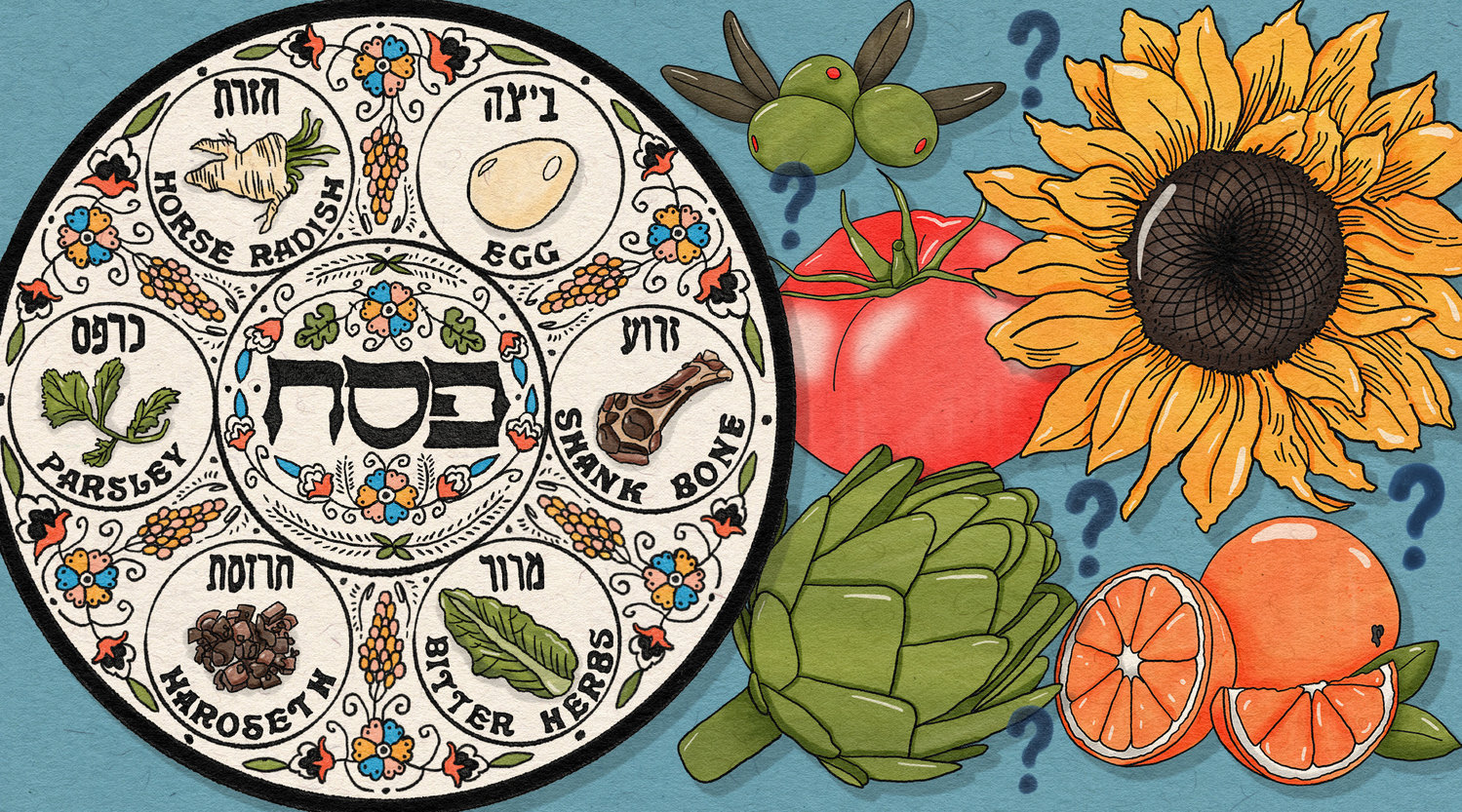

(JTA) – Olives. Tomatoes. Oranges. Artichokes. Dates. Cotton balls. And, now, sunflowers.

This list might seem like a setup for a logic puzzle or a grocery run. But it is, instead, a (non-exhaustive) list that I have seen of additions to the seder plate, items to highlight and include stories and histories that are not, at least explicitly, part of the Passover seder.

On its surface, it is a noble goal – why shouldn’t we consider the plight of Ukrainians (sunflowers), or remember the American history of slavery (cotton ball)? Wouldn’t we want to honor the farm workers who put food on our tables (tomatoes), or intertwine the story of the Palestinians along with our own (olives)? In my own family, my mother insists on the orange on the seder plate, regardless of its apocryphal origin as a feminist symbol.

But I won’t be adding anything to my plate. As a rabbi, teacher and mother, I’m sticking with the traditional items.

My decision to eschew seder plate innovation stems from the thinking about inclusion that I do all the time in my work. Both in encountering ancient text and modern community, I am always asking: Who is not in the room? Whose voices are not being heard? I know that the language I use, that we use, matters; I think carefully about the stories I tell, the translations I use, and the questions I ask. When I preach, when I teach, my hope is always that anyone, regardless of how they identify, sees themselves in the text and in the message.

At the same time, I am always aware that by naming one story, or one identity, I might be excluding another.

One of the great tensions of Jewish life in the 21st century is between universalism – the central themes and ideas of Jewish wisdom that speak to all of the human experience – and particularism, the doctrines and injunctions meant to distinguish Jewish practice and ritual from that of the rest of the world. And of all of our stories, it is perhaps Passover that best embodies this tension.

It is a story embraced by Jews, by Black Americans, by Christians the world over. It is our story, to be sure. But it is also a story for anyone, and everyone, who has ever known bondage, who has ever felt constricted, stuck in a narrow place. It is a story for all who have sought the freedom to be their fullest selves, whether that freedom is physical, spiritual, or both.

Bechol dor vador, chayav adam lirot et atzmo k’ilu hu yatza mi-Mitzrayim: in every generation, we are obligated to see ourselves as if we, ourselves, had come out of Egypt.

Core to the seder, this statement is our directive – this is how we must experience and also teach the Passover story and its lessons. We experience it as our own story; it is not simply something that happened to our ancestors, or a story of myth or history. It is ours, regardless of where we come from, who we are now or where we might be going or becoming.

The seder night is a night for telling stories, our own and the ones we think need to be told. But to my mind, we do not need more on our seder plate to make that happen. In fact, I worry that, in this case, more is less – in trying to include each particular story, we lose the universal truths. I hope that we sit around our seder tables and talk about the plight of today’s refugees, whether from Ukraine, Syria or Central America. I hope that we sit around our seder tables and talk about the bravery of each and every person who tells their coming out story and lives their truth. I hope that we sit around our seder tables and talk about the Palestinian struggle for self-determination, the ongoing struggle for farmworker and immigrant justice here in the United States, the shameful history of American slavery and its lasting legacy of systemic racism, our own stories of immigration and exile and whatever other stories you and your families need to tell.

Over the course of the seder, we lift up the items on the seder plate and tell of their significance. What is this bitter herb, we ask? It is to remind us of the bitterness of slavery, the bitterness of being subject to a power we have not chosen, the bitterness of being despised for who we are. What is this shankbone, we ask? It is a reminder of the power that can redeem us, the helping hands that pull us out of our bondage, the strength of conviction that we honor. These are particular items, to be sure, but they are telling universal stories.

Why do we need additional items, when these symbols allow us to tell the stories we want to tell? I worry that the more specific stories we attempt to include, the more we are excluding. What happens to people who do not see their specific story represented on a seder plate that is groaning with symbols of so many other stories?

One of the core lessons of the Exodus is the impulse toward empathy. Over and over, the Torah returns to this narrative, reminding us to protect and love and be kind to the stranger, because we were strangers in the land of Egypt. The Torah is not specific; we do not name that we must be kind to the Ukrainian refugee, or the trans teenager, or the Palestinian farmer, or the African man who is enslaved. Because to name one, in this context, would be to exclude another. Our empathy, the Torah teaches, is meant to be boundless and inclusive. We are to welcome anyone – and everyone – who feels out of place, who feels unmoored, who has been oppressed or mistreated.

To my mind, and in my understanding of the rites of Passover, each and every one of their stories is already represented on the seder plate and in the seder ritual. No additions needed.

Rabbi Sari Laufer is the director of Congregational Engagement at Stephen Wise Temple in Los Angeles.