Rabbi brought Benjamin Franklin’s virtues and Jewish ethical practice to Calif. inmates

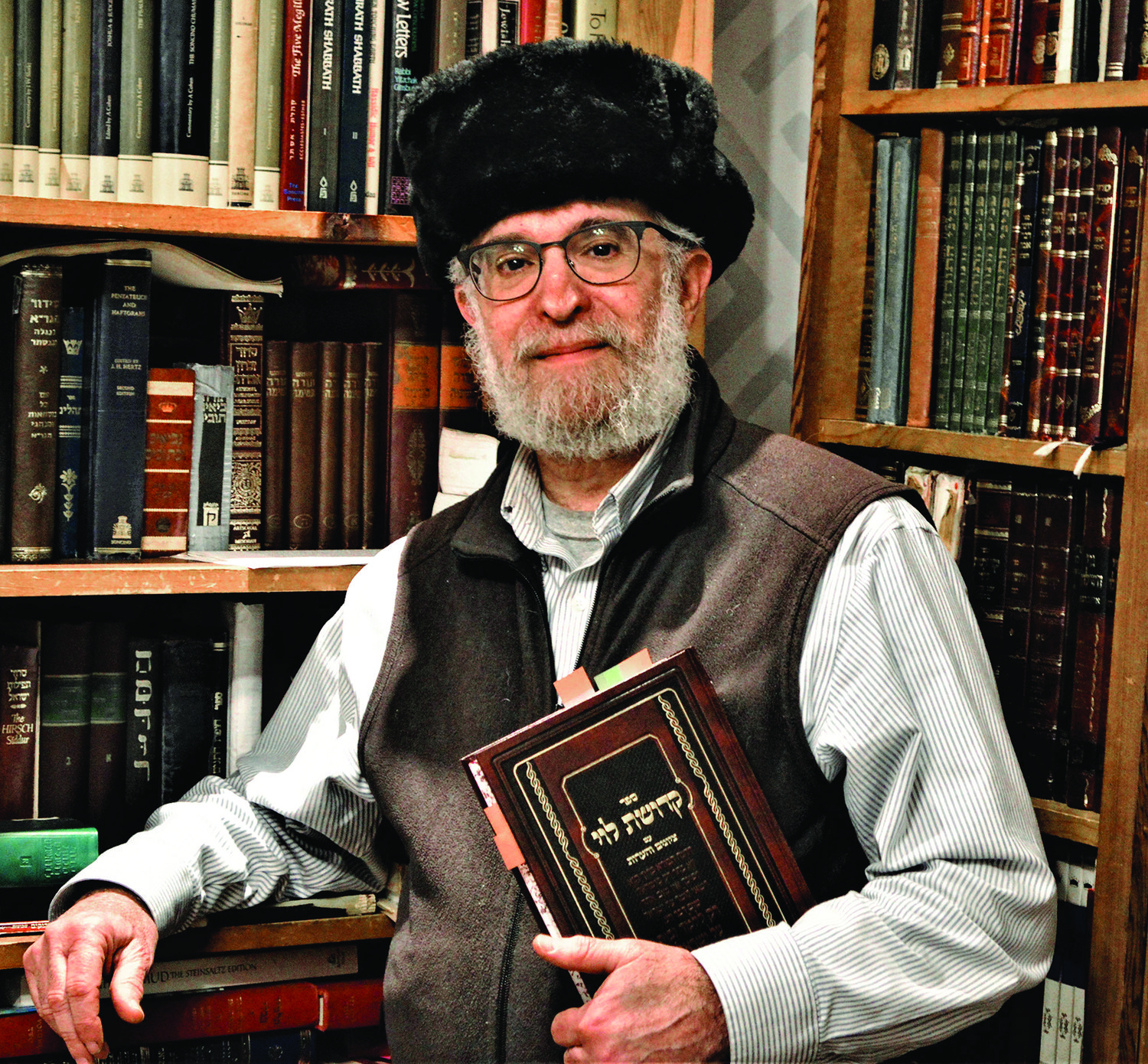

I met Rabbi Eliahu Klein and his wife, Cynthia Scheinberg, at Shabbat meals about a year and half ago, soon after they moved from Berkeley, California, to Providence, following Scheinberg’s appointment as a dean at Roger Williams University.

At one of these Shabbat meals, I mentioned to Klein that I would be giving a talk at the Rhode Island Jewish Museum/Congregation Sons of Jacob Synagogue on the link between Benjamin Franklin and mussar (applied Jewish ethics, or practical Jewish ethical instruction). This is a relatively obscure subject, but to my surprise Klein told me that he was familiar with Franklin’s influence on mussar, and that as part of his chaplaincy work in California, he had created a program for inmates based on Franklin’s virtues and Jewish ethical practice.

When Franklin (1706-1790) composed his now-famous autobiography, he included a description of a self-improvement method that he had devised when he was in his twenties. This method revolved around 13 behavioral traits that Franklin referred to as virtues (temperance, silence, order, resolution, frugality, industry, sincerity, justice, moderation, cleanliness, tranquility, chastity and humility) and to each of which, in succession, he allotted a week of close attention and reflection.

His progress and setbacks in mastering the virtues were tracked daily in a grid chart he designed, which had the seven days of the week running horizontally and the 13 virtues running vertically. After 13 weeks, Franklin began the cycle again, so that over the course of a year, each behavioral trait could be carefully worked on for four weeks.

Nearly 20 years after Franklin’s death, and halfway across the world from Philadelphia, Rabbi Menahem Mendel Lefin of Satanów (1749-1826), in Podolia, completed and published a Hebrew work based on the character-improvement technique that Franklin had outlined in his autobiography. Lefin, an early Eastern European maskil (proponent of the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment), was deeply interested in mussar, which began solidifying as a literary genre in the 11th century, as well as in bringing beneficial contemporary gentile knowledge to his fellow Jews.

Lefin’s “Sefer Heshbon Ha-nefesh” (“Book of Spiritual Accounting” or “Book of the Accounting of the Soul”), which he published anonymously in 1808, introduced Franklin’s list of virtues and character-improvement technique to Hebrew readers, though without mentioning Franklin or his autobiography by name.

Approved by 12 rabbis in its first edition, Lefin’s book – including Franklin’s technique – was soon incorporated into the mussar tradition, and became popular among Eastern European Yeshivah students.

Born in 1952, Klein grew up in Cleveland, Toronto and Brooklyn, New York, and studied at the Rabbinical College of Telshe and Mesivta of Eastern Parkway Rabbinical Seminary, in Brooklyn. He is the author of “Meetings with Remarkable Souls: Legends of the Baal Shem Tov” (1995), “Kabbalah of Creation: Isaac Luria’s Earlier Mysticism” (2000), and “A Mystical Haggadah: Passover Meditations, Teachings, and Tales” (2008).

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, I sat down with Klein for an interview, transcribed below, about mussar, his work as a prison chaplain, and his effort to introduce Franklin’s virtues and Lefin’s teachings into a California rehabilitation program.

It seems to me that the two spiritual movements in Judaism that most resonate with contemporary Jews are Hasidism [the Jewish mystical movement that began in the first half of the 18th century] – especially Chabad and Breslov Hasidism – and mussar. In Providence alone, I know of four mussar-related courses or study groups. How did you come to mussar?

I was raised in a mussar family. The origin of my interest in mussar is my father. He was a student at the Rabbinical College of Telshe, in Cleveland, Ohio. He practiced heshbon ha-nefesh [taking stock of one’s personality and conduct] using the charts in Lefin’s book, and kept a mussar diary.

My father worked on this for a time and it benefited him. I was interested in mussar to some extent, though not as much as in Hasidism. I didn’t think of “Heshbon Ha-nefesh” again until Feldheim Publishers reprinted the book [in 1996]. I was drawn to it. It was practical. It seemed like a gentle, good way to develop a radar of your inner soul.

When did you decide to also make mussar a focus of your teaching?

After 9/11, I had a big change. I’d been studying Kabbalah and Hasidism since the ’70s. By the mid-’80s, I had a group of students and we studied Lurianic Kabbalah. That group was the basis for my book “Kabbalah of Creation.” After 9/11, I really doubted everything I studied about Kabbalah. I questioned whether these were the appropriate teachings for dealing with this horrendous event. I felt at the time there had to be something more substantial people could grasp with their hearts and minds.

I was so stunned and became so numb. Kabbalah was a theoretical, esoteric teaching, sophisticated intellectually – but did it affect my spiritual growth? I wasn’t sure. I wondered: How does Kabbalah make a tikkun [repairing the world]? I felt 9/11 called for a different teaching, much closer to people’s hearts. I suddenly turned to mussar. I felt it was more fundamental in its theories that people could practice daily and see the benefit, change, refinement and purification of the body, mind and heart. After 9/11, I started teaching more mussar-style texts, and there was an interest.

Even people actively engaged in mussar study may not necessarily know about Franklin’s connection to Jewish character improvement. How did you learn about this?

Andy Heinze, who prayed at my synagogue in Berkeley, published a book [“Jews and the American Soul: Human Nature in the Twentieth Century,” 2004] with a chapter on Franklin and mussar. I read Nancy Sinkoff’s article [“Benjamin Franklin in Jewish Eastern Europe: Cultural Appropriation in the Age of the Enlightenment,” in the Journal of the History of Ideas, 2000]. I was surprised by this connection, but it made sense to me. I remembered my father mentioned, many years ago, some sort of connection between Franklin and “Heshbon Ha-nefesh.”

There was some awareness in the Yeshivah world that something in the book was from Franklin. The chart and the virtues are Franklin’s, but Rabbi Lefin’s commentary on each virtue, or midah, is based on the principles of Torah.

Why did you decide to go into prison chaplaincy?

Eventually, in 2005-2006, I pursued hospital chaplaincy training. There, I received a new type of training to help patients and their families in crisis. I had to be with people who were going through major surgeries or dying, and their families, and I had to be the kind of person who could support them. I had been asking Ha-Shem [God] to guide me to do useful work, and I found it. I helped many people pass on to the next world.

After the conclusion of the training, I chose prison chaplaincy. My prayer was to work with people I could actually transform on some level. I had a problem doing this, though. When I started prison chaplaincy, I had an agenda to get Jewish inmates siddurim [prayer books] and spread God’s light in prison – but then I met lifers who committed horrendous crimes. I had no authority to exclude anyone from Jewish services.

For many of these non-Jews, the draw to Judaism was just getting access to Kosher food, in which food items are individually packaged and can be bartered or sold. I wondered: What am I doing in the prison? And what I found out is that there were all kinds of people aside from Jews that were doing their versions of teshuva [repentance] that I hadn’t thought about.

Was it this realization about non-Jewish inmates being engaged in forms of repentance that gave you the idea of using Benjamin Franklin and mussar in the prison setting?

After the U.S. government federal receivership took over the California prison medical system in 2006, the warden at the Deuel Vocational Institution, in Tracy, California, reached out to chaplains to create rehabilitation programs. One of the chaplains suggested a program focused on imperatives for successful parole, and I came up with the Practicing Ethical Values program, which was turned into a DVD and shown to all incoming inmates.

I designed the program, an inmate named Mike D. and I selected the virtues [from Franklin’s autobiography and Lefin’s “Heshbon Ha-nefesh”] and he constructed the categories [i.e., Being/Personality Traits, Living/Life Skill Traits and Action/Social Responsibility Traits].

The reason why I wanted to create this program was because I discovered that there was no actual program for inmates to literally work on themselves, on the issues that may have brought them there. After talking with a lot of inmates, I got the sense that few of them had societal or familial familiarity with ethical values.

What made you think mussar could be a good conduit for non-Jews to engage with ethical values?

There are other true paths that can change your perspective of how to be or not be in the world. But I had the goal of teaching a form of Judaism I believed in. Using the charts from Benjamin Franklin and “Heshbon Ha-nefesh,” you develop a heightened awareness that creates change in a natural way, and I thought these inmates could benefit. It’s a very easy way to monitor how you react and respond to people and situations. I saw it would be very wise not to have the program come across as totally Jewish, but to also focus on Benjamin Franklin: “Even Benjamin Franklin worked on himself, and you can too!”

How was this Franklin and mussar program received?

The warden went for it, and it was very successful while it was going on. The inmates cooperated and shared their struggles and growth. Nine guys went through the whole program. They were lifers or long-term inmates who had a desire to change.

When I asked the guys that took the full course what motivated them, most said it was the power of Jesus. I was trying to divorce it from religion, but the reason many of these people are alive is because they made a commitment to deep religious practice. Their new belief systems turned them around.

Did you gain a new perspective on mussar from working with these men?

In the final analysis, I discovered that the mussar movement [a movement centered on character refinement and the concentrated study of mussar texts, which was begun by Rabbi Yisrael Salanter in Eastern Europe in the 1840s] was truly a universal path that could benefit anyone from any ethnic and religious tradition.

SHAI AFSAI (shaiafsai.com) lives in Providence. His “Benjamin Franklin’s Influence on Mussar Thought and Practice: A Chronicle of Misapprehension” appeared in the Review of Rabbinic Judaism 22:2 (2019). That article, along with the above interview, was completed with support from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. A longer version of the interview was published in the May 18, 2020, issue of The Jerusalem Report.