Reinterpreting the Binding of Isaac

Nineteen verses tell the story of the Binding of Isaac – read in synagogue each Rosh Hashanah – but there are hundreds, if not thousands, of commentaries on it.

Nineteen verses tell the story of the Binding of Isaac – read in synagogue each Rosh Hashanah – but there are hundreds, if not thousands, of commentaries on it.

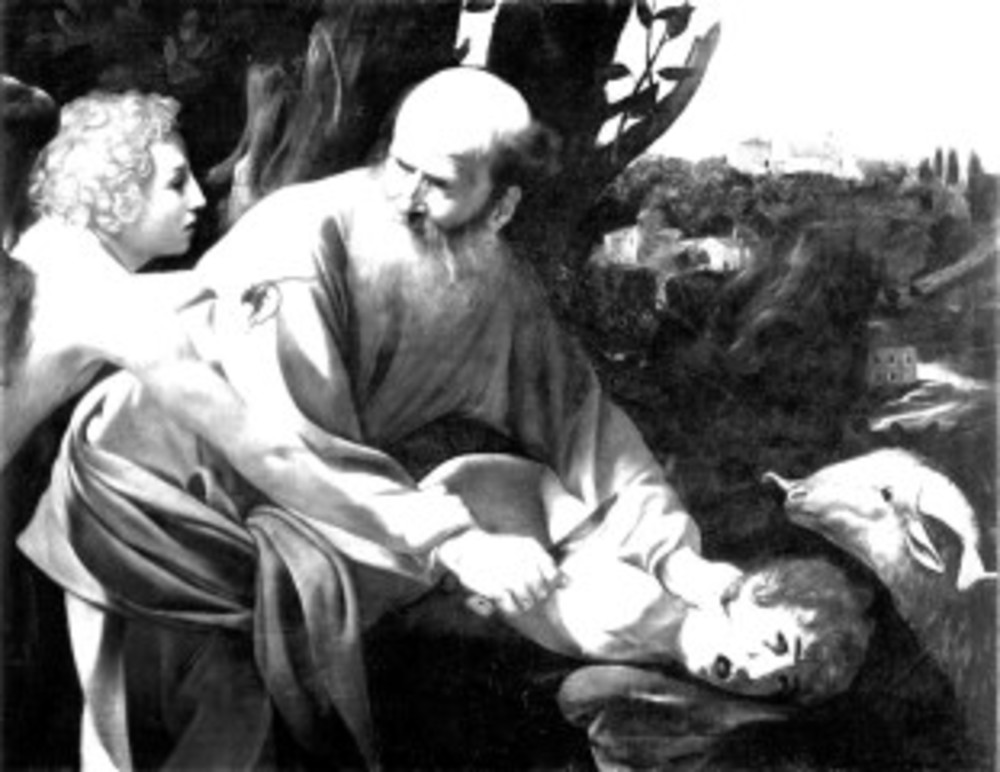

Commentaries ask: How could a good God command a father to kill his child and how could a good father possibly obey? What was it like on the three days when Abraham and Isaac journeyed together toward the place where the sacrifice would take place? Did they talk along the way or ride in silence? Did Sarah know? In this age of jihad and suicide bombers who train their children to be killers and martyrs for the sake of Allah, how can we still read this story, which seems to praise murder in the name of God?

The nuances of every word of the story – and of the silences – have been studied in every generation. Yet every Rosh Hashanah, when we confront this awesome tale, we wince.

Fathers wonder: Could I do this to my child? Sons wonder: Could my father do this to me? We all wonder: What kind of a God is this? We ask ourselves: Why do we read this on Rosh Hashanah?

James Goodman’s new book, “But Where is the Lamb? Imagining the Story of Abraham and Isaac” (published by Schocken Books, in New York City, 2013), offers a fresh and exciting perspective on interpretations of the Binding of Isaac. Writing as a son and a father, as a Jew and a person in search of meaning, Goodman is a storyteller fascinated by this ancient tale.

It is impossible to determine exactly where a story has its origin, because every story has a story that came before it. Goodman imagines a writer whom he calls “G,” who was asked to do a rewrite of this story, but who turned it in to the editors before he was completely satisfied with it. G wanted to struggle more with the silences in the story, but the editors took it away from him and published it before he could finish it.

Then G learned the lesson that every writer must learn – once you have published a story, it no longer belongs to you. Every reader who picks up your tale has the right to see in it whatever it means to him.

For the author of the Book of Jubilees, the Binding of Isaac was a precursor to the Passover story, in which the Israelites were rescued at the last minute by the sacrifice of a lamb, and the purpose of the story was to show the envious angels why Abraham was worthy of being so beloved by God.

For Philo, who wrote in the midst of Greek culture, Abraham was a stirring example of stoicism. He understood Abraham as a noble example of the wise man who suppresses emotion for reason.

A weaker man might have wavered or cried, or been struck dumb by Isaac’s question, “Where is the lamb?” But Abraham showed no weakening. He remained steadfast, as befits a true stoic.

For Pseudo-Philo and for the second book of Maccabees, Abraham was the prototype for parents who surrendered their children to martyrdom in the time of the Hellenists. For the early Christians, the story became a preview of the story of Jesus. In Sarah, they saw Mary.

In Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, they saw God’s willingness to sacrifice His. In the three-day journey, they saw a prefiguration of the three days from the crucifixion to the resurrection. In Isaac’s carrying of the wood, they saw Jesus carrying the cross. In the ram caught in the thicket, they saw the crown of thorns. In the whole story, they saw the supremacy of faith, and themselves as the new Israel that replaced the old one.

Chapter after chapter, Goodman’s book teaches us what the generations read into and out of the tale. As Goodman says, you feel like an observer at a great convention, at which scholars and sages of all generations exchange insights into what the ancient tale means to them.

You see people who read the story in Hebrew sitting next to people who read it in Coptic or in Aramaic, Greek or Latin, all comparing notes. In one corner, a newcomer to Islam carries the Koran that says that it was Ishmael, not Isaac, who was bound upon the altar; in another, a midrashic sage firmly believes that Sarah should have been informed of what was going on.

In the center of the room the Sages of the Talmud insist that the Binding of Isaac was an achievement that God promised He would always remember, and that, because of what Abraham and Isaac did that day, God would always care for His people. The poets of the Crusades dare to say that Isaac died on the altar that day, but then came back to life.

The book lets us in on the conversations of Soren Kierkegard, Wilfred Owen, Shalom Spiegel, A. B. Yehoshua, Bob Dylan, Yitschak Lamdan and others closer to our own time.

I come away from this book with a sense that the conversation about the Binding of Isaac is not over. This Rosh Hashanah, who knows what we may yet find in this fascinating tale that has the capacity to surprise us?

Rabbi Jack Riemer writes frequently for journals of Jewish thought.