Sons of Jacob president is looking for an angel

PROVIDENCE – On a recent rainy morning, Harold Silverman, president of Congregation Sons of Jacob, stood in the shul’s vestibule and gestured toward three windows. The half-circles of glass had been removed from the wall and stood on a bench and the floor. The first had a broken frame and a single, dislocated glass pane. The second was weathered, but intact. The third window looked as though it had been fully restored, with clear glass and freshly sanded wood.

The message was clear: Time has been unkind to Sons of Jacob, leaving the red-brick Smith Hill building a shadow of its former self. Shattered windows, peeling paint, ragged carpet – all its decor has fallen victim to the elements or passing vandals with rocks.

But if Silverman can raise $1.75 million, the building could be improved, like that second window. And if he raises more – say around $5.2 million – the 127-year-old structure could be fully restored, like that third window.

“We need an angel,” Silverman says.

Silverman, of North Providence, doesn’t like to talk about himself. He won’t reveal his age, saying only that he’s “old enough to know better.” He won’t delve into his career in electrical engineering or the particulars of his personal life. He deflects probing questions with witty comments, or else he says, “That’s not important. None of this is about me.” He even declined to be photographed for this article.

When pressed, Silverman speaks breezily of his early years in Flushing, New York, before his family inexplicably moved to South Providence when he was 10.

To Silverman, the relevant part of his life began in 1972, when his mother passed away; he sought an Orthodox synagogue where he could say the mourners Kaddish.

“There was no synagogue I could rely on for a year of mourning, except for Sons of Jacob,” he says.

Still, Silverman had to get reacquainted with the Orthodoxy of his youth.

“[I felt] isolated. I didn’t know anything,” he says. But, he added, by relying heavily on the congregation’s guidance, he regained his spiritual footing.

Silverman never aspired to the position of president of the shul, a role he has held for many years.

“I was forced into it,” he says with an impish grin. “The older people said, ‘We can’t do it anymore.’ ”

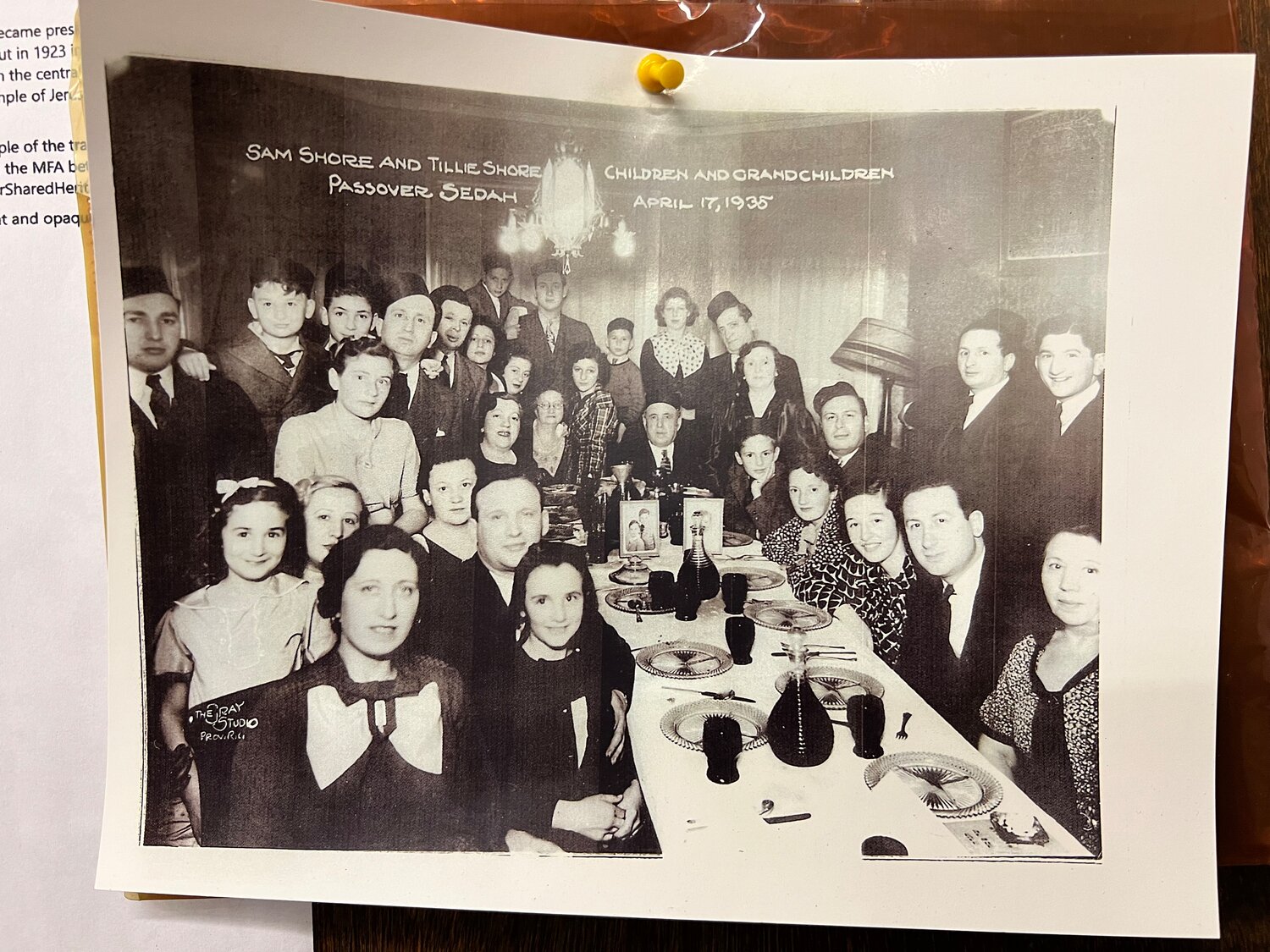

As private as Silverman is about his own life, he’s effusive about the synagogue. He beams as he leads a tour through the building, showing off every nook and cranny and explaining their significance. Here is an intricate paper-cut picture, snipped into existence by congregant Sam Shore in 1923. Over there is a picture of Shore and his extended family at a dinner table; the caption, nodding to the Rhode Island accent, reads: “Passover Sedah, April 17, 1935.”

Silverman pulls back a panel and reveals a complete set of Talmudic volumes, dating back to the 18th century. He presents three Torah scrolls, provided by the Sisterhood of the Sons of Jacob.

“The Torah, that’s the whole thing,” Silverman says in a reverent tone. “The aura of God, and the love of him.”

Most stirring of all is a chalkboard, positioned near the back, where “Happy New Year” has been written in Hebrew. The message was from Rabbi Moshe Drazin, who oversaw Sons of Jacob when Silverman first arrived, and who passed away in 2004.

“I won’t erase it,” Silverman says.

There’s also a black-and-white photograph of the white-bearded Rabbi Drazin near the front entrance, with a handwritten note proclaiming: “A noble and proud Jew. A prince among men.”

All of this appears on the first floor of the building, which was completed in 1906 and includes a kitchen, dining area and upright piano. This is the modest, basement-like space that remains open, inviting congregants and visitors to pray in the early morning hours, on Shabbat and on holidays.

But climb one of the two staircases – separated by gender – and there’s far more. As Jewish immigrants continued to trickle into the neighborhood, Sons of Jacob grew: A massive second floor was completed in 1926. This large auditorium holds rows and rows of pews and has a wrap-around mezzanine. The ceiling is painted with figures from the Jewish Zodiac. A large monument is embossed with all the names of Sons of Jacob members who served in World War II.

A large menorah rises in the middle of the bimah, and hundreds of bulbs on the far wall can be switched on to mark a yahrzeit.

This is the most splendid room in the synagogue, a testament to the 380 families who once worshipped here, yet it’s also the most wounded. Windows are broken. Plaster is worn. One entrance has been barred with planks of wood, to prevent vandals from breaking in.

Sons of Jacob replaced the roof in 1999 and upgraded the heating and electrical systems in successive years, but the extremes of the New England climate have still left their mark. The heating system doesn’t warm enough in winter, and summer humidity has wreaked havoc on the walls. Services in this space ceased about 10 years ago, and the 30 remaining families of the congregation have retreated to the first floor.

“Humidity and the heat,” says Silverman. “If we can handle that, we can start to paint and plaster. Just make the building usable. That’s it.”

Indeed, Silverman isn’t asking for the moon. The temple’s total annual budget is about $35,000. This almost always falls short by about $4,500, which the endowment usually makes up for. But now, the endowment is “pretty well extinguished,” Silverman said.

The synagogue survives largely on $75-per-year family memberships and donations left in the tzedakah box. It also receives gifts from Hasbro and the Dwares family; Hasbro cofounder Israel Hassenfeld and many members of the Dwares family, the namesake of the Alliance’s Dwares Jewish Community Center, were prominent Sons of Jacob members. But all of this remains modest, far below the $1.75 million minimum that the congregation needs.

Money won’t solve all the problems, of course. One of the cruelest events in the synagogue’s history was the construction of Interstate 95, which steamrolled through the largely Jewish community and dislocated its residents. Today, the building, at 24 Douglas Ave., stands on an obscure spit of land, barely visible from the nearby intersection. Worn triple-deckers and roadside tents set the tone of the neighborhood. This affront goes back 70 years, and not even Silverman’s hoped-for angel can reverse the highway’s damage.

But Silverman has come up with a striking solution – or at least the early brainstorm for one. The Sisterhood of the Sons of Jacob was founded in 1940 and remained active until the late 1990s. A plaque on the first floor commemorates “their leadership, devotion, and faithful service.” The three Torahs were a gift from the Sisterhood, among countless other achievements in the shul’s history.

Reviving this kind of Sisterhood, posits Silverman, could reenergize the congregation; instead of 30 families and a handful of visitors, a women’s organization could invite fresh interest.

“We need a Sisterhood,” Silverman concludes. “Where the women go, the men and families will follow.”

What the future holds for Sons of Jacob is anyone’s guess. The shul sends out letters, explaining the need for donations, but they haven’t hosted a fundraising event in years.

Silverman is friendly with other congregations and Jewish leaders, but doesn’t report much support. As one letter from 2018, requesting a grant, put it: “All positions [at Sons of Jacob] are volunteer, including the Rabbi.”

Yet Silverman still sounds hopeful. He speaks plainly about the challenges, without once entertaining a worst-case scenario. So much of his life is woven into the story of the synagogue, the two narratives seem nearly interchangeable. He might have been coaxed into the role of president, but looking back, would he have had it any other way?

Silverman flashes his characteristic grin.

“Well, I’m still here,” he says.

ROBERT ISENBERG (risenberg@jewishallianceri.org) is the multimedia producer for the Jewish Alliance of Greater Rhode Island and a writer for Jewish Rhode Island.