The cost of denial

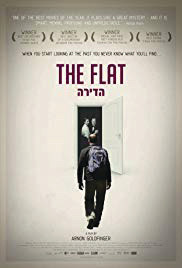

When my wife, Sandy, and I sat down this past fall to view the 2011 Israeli film “The Flat” (“Hadirah”) on Netflix, we had no idea that we were about to see a documentary of extraordinary power and complexity — a 93-minute detective story that uncovers family secrets arising out of overlapping and conflicting identities.

What the filmmaker had begun to shoot as a home movie evolved into a five-year project that came to involve German-Israeli artistic collaboration, including the participation of the independent Berlin-based production company, Zero One Film.

Shortly after its debut in July 2011, at the Jerusalem Film Festival, Israeli film critic Avner Shavit praised “The Flat” as “one of the best Israeli documentaries ever made.” Over the next couple of years, “The Flat” — in Hebrew, English and German, with subtitles — accumulated award after award in Israel, the United States and Germany, as well as in a number of other countries.

After Gerda Tuchler died, in Tel Aviv, in September 2006, at age 98, one of her many grandchildren, Arnon Goldfinger, at the time 43 years old, took it upon himself to preserve on film the contents of his grandmother’s elegant apartment (the “flat” of the title). His grandmother had lived in those very same rooms for 70 years, ever since she and her husband, Kurt, came to Israel from Germany in 1936. After Kurt died at the age of 84 in 1978, Gerda remained there by herself until her death 28 years later.

Goldfinger tells viewers that he always enjoyed visiting his grandmother’s apartment because it was like walking into a foreign country — specifically, the German city of Berlin. The bookcases were lined with books written in German; Gerda had never learned to speak, read or write Hebrew.

To add to the sense that she had never really left Germany, Gerda had managed to preserve the atmosphere of her native land through her decorating style. It would seem, then, that among Goldfinger’s reasons for documenting his grandmother’s belongings was to preserve for his extended family not only memories of Gerda but also memories of her vanishing world.

“The Flat” begins innocently enough, with the uncovering and tossing out of bags full of old-fashioned shoes, gloves, pocketbooks, even those creepy fox fur scarves with head, tail and legs preserved intact.

But soon the process of emptying the apartment takes an ominous turn: a family member comes across a 1934 issue of a virulently racist Nazi newspaper, Der Angriff (The Attack), which details a two-month trip that a Nazi member of the SS, Leopold von Mildenstein, had taken the year before to what was then Palestine, along with his wife and a German-Jewish Zionist couple. Ironically, in 1933-1934, Nazi and Zionist aims were briefly congruent: the Nazis wanted the Jews out of Germany, while the Zionists wanted to bring as many Jews as possible to Palestine.

What turns everything upside down for Goldfinger is the discovery that the Jewish couple traveling with the von Mildensteins from Germany to Palestine were none other than his grandparents, Gerda and Kurt Tuchler!

As Goldfinger digs deeper into the relationship between his grandparents and the von Mildensteins, he discovers, to his dismay, that they had become good friends before the war and, even worse, continued their friendship after the war, even after the Holocaust had consumed his great-grandmother, Gerda’s mother, Susanna Lehmann.

Much of “The Flat” is a record of Goldfinger’s attempt to answer a series of deeply painful questions: How could his grandparents remain friends with a man who, it turned out, served the Nazi regime in Goebbels’ Department of Propaganda? How could his mother, Hannah, maintain her professed indifference to her parents’ ongoing friendship with a Nazi — a man who bore responsibility, though indirectly, for the murder of her mother’s mother? And how could von Mildenstein’s daughter, Edda, whom Goldfinger visits on two separate trips to her home in Germany, refuse to accept the fact that her father worked for Goebbels during the war, even after Goldfinger presented her with conclusive evidence from archives in what used to be East Germany?

Though Goldfinger attempts to answer these questions during the course of his documentary, he is, at best, only partially successful. In an interview with Cindy Mindell, which appeared in the April 1, 2015, online issue of the Connecticut Jewish Ledger, Goldfinger is still struggling to make sense of these troubling behaviors:

“… I don’t see my grandparents as Israelis. My grandmother lived in Israel for 70 years; when she left Germany, she was 28 years old. But she was not an Israeli who was born in Germany. The one thing that became very clear was that she was a German who lived in Israel …. My grandparents and many other German Jews of their generation were Zionists; but, in many respects, they lived in Israel in exile. They couldn’t mix with the new Middle Eastern Israeli culture ….

“I think for them the relationship with the von Mildensteins could play this way: ‘… We’re Jews, they’re Germans, not all of the Germans were so bad — maybe not all of the Nazis were so bad.’ Of course, it’s a play of denial. The main psychological issue in the film is a search for this denial mechanism in all kinds of territories and characters.”

The last words in “The Flat” are spoken by Goldfinger’s mother, Hannah, as the two of them are wandering through an overgrown Jewish cemetery in Germany, searching for the grave of Heinrich Lehmann, deceased husband of Hannah’s murdered grandmother, Susanna: “There used to be many graves here, but now they’re all gone.”

Hannah’s words suggest that the cost of denial is that the truth of the past can never be recovered.

JAMES B. ROSENBERG is rabbi emeritus of Temple Habonim, in Barrington. Contact him at rabbiemeritus@templehabonim.org.