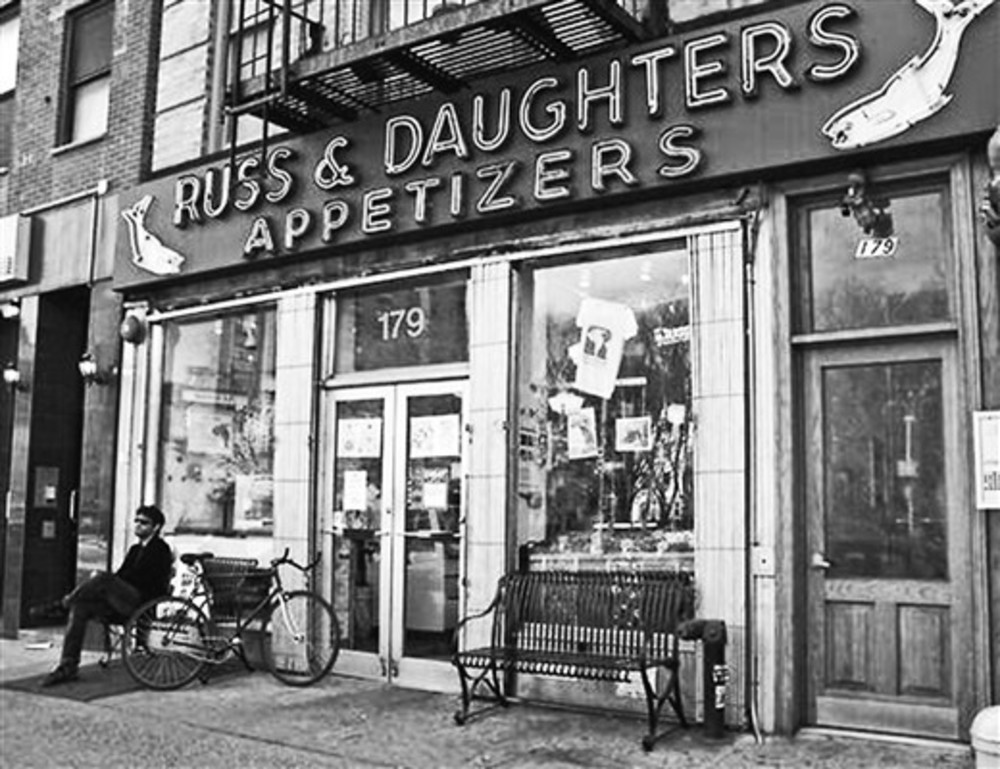

The herring monger of the Lower East Side

Storefront of Russ & Daughters. /Russ & Daughters“This little old Jewish lady approaches me and demands I go behind the counter and make her a herring!” Mark Russ Federman’s vignette illustrates the type of old-timey customer that still shows up at Russ & Daughters once in a while. A grandson of the original owners, Federman has been retired for five years after having run the store for three decades. Even though he passed on the business to his daughter and nephew, that doesn’t stop the regulars from asking him to serve them.

Storefront of Russ & Daughters. /Russ & Daughters“This little old Jewish lady approaches me and demands I go behind the counter and make her a herring!” Mark Russ Federman’s vignette illustrates the type of old-timey customer that still shows up at Russ & Daughters once in a while. A grandson of the original owners, Federman has been retired for five years after having run the store for three decades. Even though he passed on the business to his daughter and nephew, that doesn’t stop the regulars from asking him to serve them.

He continues, “The place is packed. She doesn’t want to take a number because she feels that the store is hers, and we’re there to take care of her.” The lady doesn’t care that Federman no longer works there, that filleting a schmaltz herring takes too long or that they don’t perform that process on the counter anymore. She wants nothing to do with the herring that the kitchen help has already prepared and placed on the tray.

Federman pulls out his trump card, asking the woman, “Madam, do you know who I am? I am Mr. Russ.” The lady is unimpressed, “I know you. Your grandfather was Mr. Russ.” Nothing left to do but make her a herring. Federman explains that there’s no point in arguing with the loyal customers, who feel they have a proprietary interest in the store. It’s better to follow his family’s mantra, which – translated from Yiddish – loosely means, “How do we survive?” This approach has served them well through the years.

Federman’s description of what it’s like to run the store epitomizes a Catch-22 situation. Success means always moving forward; however, how does the owner advocate advancement when the customer perceives even the slightest change as existential? Federman says the regulars get bewildered if they notice that a product has been moved. He’d hear admonishments such as, “Your parents never put it there!” In a traditional generational shop, “the customers must be constantly reassured that the world will not come to an end.” When, in 1978 he left a career in law to run Russ & Daughters, he didn’t realize how hard it would be to blend into the milieu of the delicatessen. Federman came into the shop thinking that he’d easily systematize the process to achieve ultimate efficiency. What he learned, however, was that his parents and grandparents were a lot smarter than he had thought. While they were not great at articulating their ideas, they had an experiential sense of running the business. He says, “Their way was almost always the right way to do it.”

Federman struggled to explain why he left law to work at Russ & Daughters. He even wrote a book (“RUSS & DAUGHTERS: Reflections and Recipes from the House That Herring Built”) hoping that would help. Federman admitted that his foray into the family business was ironic in the sense that his parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles never wanted their children to work as hard as they did. They dreamed that their kids would work five days a week behind a desk, not smelling fishy when they came home. And, of course, the ultimate Jewish immigrant’s dream was that the children would become professionals. Federman says that, while all seven of the Russ grandchildren were college-educated, he was the only one to emerge as a professional. He was also the only one to take over the family business.

Federman said he stayed with the shop because Russ & Daughters was a special place for him. Since he was a child, Federman was required to work at the store. Through the years, he has internalized the knowledge that the shop was a good thing to keep going. While he never felt comfortable practicing law, at the store, he “felt like [he] was adding some value to the world.” Like his parents, he was establishing relationships that transcended commercial transactions.

In the ’70s, Federman was a one-man operation devoted to the store. When he took over the shop from his parents, he remembers that the Lower East Side neighborhood was experiencing a downward spiral. Federman’s challenge was to make sure that the customers stayed loyal despite their fear of being mugged or having their car broken into. He explains that most of the shops moved either uptown or downtown, so it was a challenge to entice the customers to visit the area just to shop at Russ & Daughters. Unlike now, when high rises dwarf tenement dwellings, and the customers say please and thank you, this was a tougher world where the customers really made you work for their money. While current clientele doesn’t mind taking a number and waiting, the old customers were hard and gritty; they believed that spending their hard-earned money entitled them to say what was on their minds, and they didn’t mince words, letting you know you worked for them. Once the relationship was established, they became fiercely loyal, akin to family.

Little by little, the regulars became used to the risks Federman was taking. For instance, when he hired two Latino workers to stand behind the counter, some customers took issue with the change. After all, this was a Jewish store in a Jewish neighborhood selling Jewish food to Jewish people! But observing the deferential “Dominican boys” slice the salmon in an artistic way and hearing them speak Yiddish, the regulars understood the appeal.

Nowadays, even tofu cream cheese finds acceptance. While the old customers are an endangered species, as Federman calls them, the new ones still appreciate the straightforward products that taste good. New York welcomes hordes of Europeans who are not only grateful and patient, but also contain this food in their genetic makeup. No matter where they’re from, the immigrant story is their story.

If you aren’t a frequent visitor to New York City, and yet the name Russ & Daughters is a familiar one, you might have read about the popular delicatessen in the media. Lately, news of the shop has been all over the place. In addition to the hype surrounding Federman’s book, newspapers have run reviews of a recent documentary on the store. Because so many relate to the tale of a family from a poor shtetl in Eastern Europe the film “The Sturgeon Queens” has become popular. Featuring 100-year-old Hattie Russ Gold and her sister, 92-year-old Anne Russ Federman, the documentary is a brainchild of Julie Cohen. In 2007, she chose the store as one of the six subjects she was filming for a New York PBS documentary called The Jews of New York. The segments, which shared stories of Jewish families who went from immigrant status to an iconic one, proved popular.

Federman explains that the director fell in love with the two feisty yet warm women while filming. It’s not hard to believe if you watch the trailer of the documentary, which seems hilarious and entertaining. Because she has never gotten such positive feedback as she did from the food segment of the original film, Cohen decided to expand the segment beyond the 12 minutes. She added some already existing footage and interviews with family members and celebrities who love the shop. The first five famous people Cohen asked agreed to participate right away. Among them is Ruth Bader Ginsberg, who offers memories of visiting the shop with her mother. Referring to the public’s reception of the store and to its status among New Yorkers, Federman says, “You can’t buy that kind of thing!”

He still doesn’t regard himself as a celebrity. Categorizing himself under “the transitional generation,” Federman says he has inherited his family’s Depression mentality. He’s cautious – his eye is always on the register, and his hand is always clutching a rag in his pocket. Yet, he’s still the “herring king of the Lower East Side.” The herring is no longer déclassé as it once was. The new customers love its strong smell and the fact that it allows for different preparations. They visit the newly opened café, where they can sit, relax and savor the salty fish, along with other beloved delicacies.

Federman acknowledges that Russ & Daughters is seen as a legendary institution and even enjoys the sudden sparks of recognition. In a recent encounter, a woman, who – upon learning who he was – told him that her day can’t get any better. Federman says, “I make people feel good. I don’t want to jinx it – I’m blessed.”