There’s one in every family …

“Every family has a strange aunt.” I borrowed that phrase from a book titled “Was Elvis Jewish?” by Paulette Cooper, a Holocaust survivor I once knew. I use the phrase as a way of saying that there are no perfect “nuclear” kith and kin realms – which brings me to the only relative that I have ever cast aside.

“May your name be scattered in the wilderness” is a terrible Yiddish curse, and I therefore use no first, middle or last name, and no image, to identify this person, except the tale of her place in my life. If any snapshots existed, I have not kept them!

She was once a frequent guest welcomed in our home with her husband and two sons, my cousins. I was somehow a bit afraid of her: She resembled the fearsome pirates staring from the murals in our lively cellar, giant illustrations from “Treasure Island,” and she smoked cigarettes that hid her eyes and disguised her expression.

During two “duration” summers – in 1942 and 1943 – my brother and I were sent to her summer camp in Maine, where I continued to be scared by her routine entrances into the bunk to ask, “Did you move your bowels today?” So intrusive, aggressive, judgmental about such intimate things.

I got used to her, however, and grew to admire her political opinions about important matters. She was a member of the American Civil Liberties Union and, I believe, a card-carrying Communist. In high school, where I joined the Debating Society, I was proud of having so active and articulate an aunt, and brought my classmates to meet and greet her.

After our first college semester, my brother and I served as counselors in another lakeside camp she owned and ran, in the early midcentury, the Communist “witch-hunt” years that produced the execution of the Rosenbergs, Julius and Ethel, leaving their boys to be adopted.

Her brother announced his engagement, and our boyhood home served as a happy haven for tea or sherry, a place where relatives and guests could toast and celebrate together. My “political” aunt behaved in a manner that shocked me.

“My brother is not mentally capable or competent and has no business entering a marriage!”

She declared this, and, adolescent though I was, I dared to counter her statement with whatever defense I was able to articulate.

In 1953, I returned to her camp as a counselor, along with a classmate and chum of mine and my brother’s, despite a warning from a close friend that this familiar person, my father’s sister, often turned on people with a sudden ferocity, a fierce but inexplicable vengeance.

My father’s half-brother, and therefore her half-brother as well, was working as the arts-and-crafts counselor, and his wife and two small boys were also at the camp, so I felt safe and secure.

I had the youngest boys in my cabin, and I befriended the camp nurse. I was also the birdwatching nature teacher, and I contributed my collections of bird nests and bird cards with information from the Audubon Society to the special hut that served as a natural history museum.

I had a brief bit of a romantic interlude at a nearby pond with a pleasant, smiling Jewish girl who sketched our encounter ... and visited my family homestead during a mid-summer break.

Then one day, there was a bus trip to a mountain lodge for an adventure in climbing and setting up a tent. I was suddenly told that I was not invited! I was shocked and profoundly disturbed when I realized that I was an outcast, with no idea in the world what I had done to merit such an exile.

My little campers trusted and loved me, and their mothers and fathers not only invited me to their homes, but during my forthcoming junior year in Paris, the father of one of those wee campers came to visit and took me to dinner on the Champs Elysees!

I made my way home, where my uncle immediately explained to my mother and father that my aunt had gone quite mad!

Needless to narrate, I never spoke to her again. If we met on the street here in the tight quarters of the East Side of Providence, we ignored each other. My mother would turn her back on her sister-in-law should they find themselves together at a family function.

This aunt said of my brother and me, a dire announcement: “They’re made of nothing and will come to nothing!” Did that imply we were somehow fragile and doomed, unlike her strapping boys?

During the Vietnam War decade, she had disowned her own clan and moved out of the U.S.A. to Toronto, Ontario, over the border in Canada, thus disappearing from my community … until a dramatic event created another episode in this story. My mother had died, and we were sitting shiva in the parlor when another aunt – the half-sister of the aunt who is the focus of this piece – said that “she” was at the front door, about to enter.

What did I do? I went through the vestibule to the brick front stairs and said, “You are not welcome in this house. My mother would not have allowed you, and I will not permit it in her honor. Next week you may come in, as my father’s sister, but not during this time of mourning.”

The aunt who had told me that “she” was there on the stoop was proud of me for my courage and candor, and told me so several times. “I was always afraid of her, but you were right to put her in her place.”

My dad went out to her car briefly as a minimal courtesy.

Later, during a “wintersession,” my colleague and I interviewed that uncle who had been so cursed by his sister, and his wife and son. I read a letter he had received from her. “Do not come to see me or write to me,” it said. “I am no longer your sister. Go away. Move to Israel. Leave us alone.”

My colleague was appalled, but fascinated, by the intensity of this battle of words between two siblings.

Perhaps I can explain it, or maybe not. You see, when this uncle was born, his/their mother died. The birth presaged a death. This uncle was a devout and dedicated orthodox Jewish semi-orphan, in an assimilationist family that had lost respect for ritual. He was distressed, but during World War II he proved his patriotism nobly as a medic capable of saving lives and protecting the wounded. I loved him for his profound kindness.

His sister may have blamed him for their mother’s death, but my conclusion is that there is no “normal” or “typical” family history. In some poetic sense, we are all orphans seeking a lost ancestry of affection, regard, respect and dignity.

One last glimpse from my memory: I am a graduate student at Harvard and my aunt’s elder son is an undergrad. I am stepping into the Widener Library and there he stands. He steps toward me with a look not of surprise but of kindly remembrance as he greets me with an amiable smile. A nostalgic expression that heals … that helps to end this account and seals it with a silent understanding without need of words.

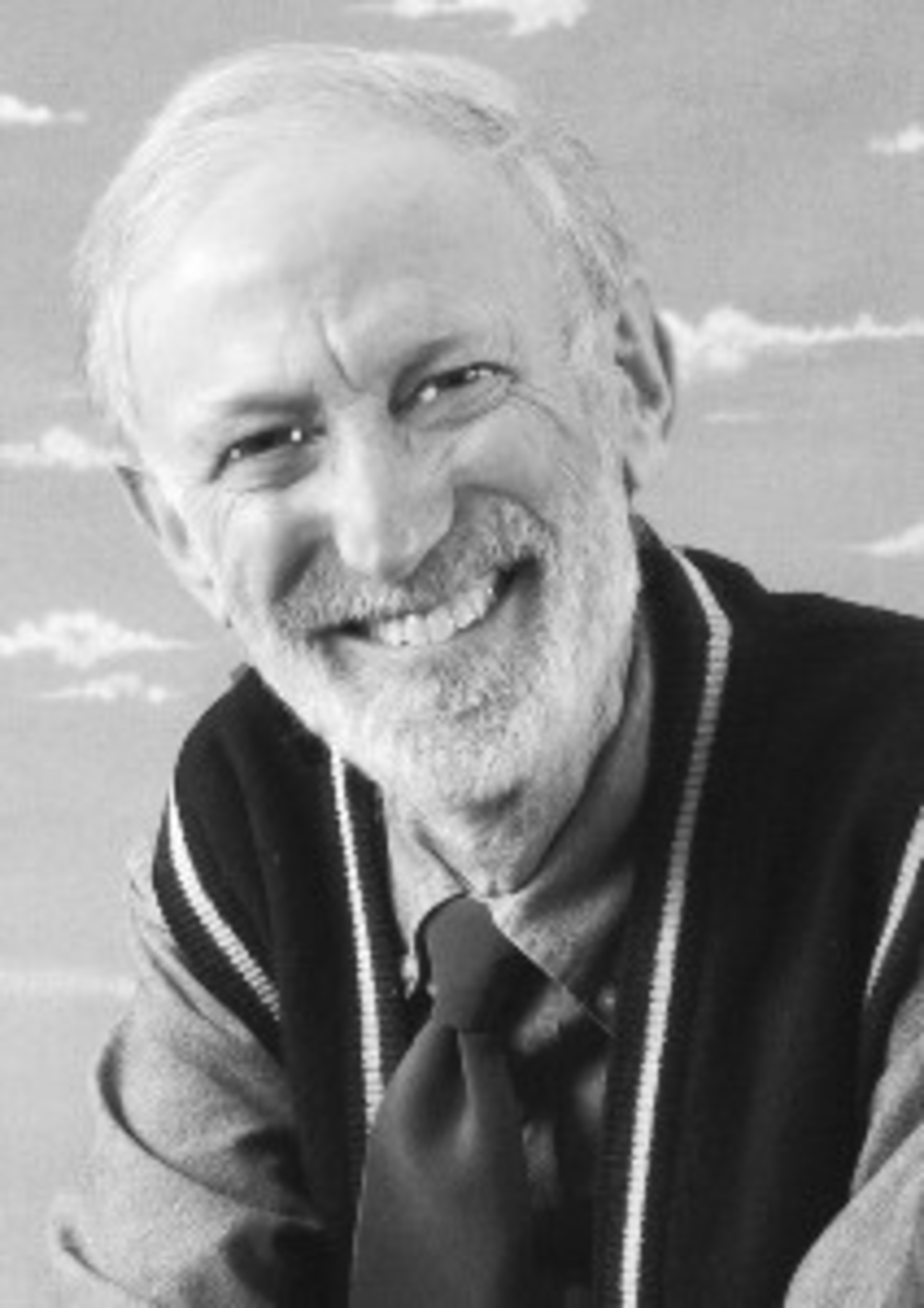

MIKE FINK (mfink33@aol.com) teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design.