Town hall meeting addresses living on the edge

Battling financial adversity: it takes a village

Most New Englanders have attended town hall meetings during which the locals participate in an informal public forum, voicing their opinions and asking questions about issues relevant to the community. The reason for the Alliance Town Hall Meeting on January 16 was to better understand the economic challenges and needs of the Greater Rhode Island Jewish households, as acknowledged in a recent study.

Most New Englanders have attended town hall meetings during which the locals participate in an informal public forum, voicing their opinions and asking questions about issues relevant to the community. The reason for the Alliance Town Hall Meeting on January 16 was to better understand the economic challenges and needs of the Greater Rhode Island Jewish households, as acknowledged in a recent study.

More than a year ago, the Jewish Alliance of Greater Rhode Island, with the support of Alan Hassenfeld, commissioned the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University to examine the economic status of Greater Rhode Island’s Jewish community. Jeffrey K. Savit, president and CEO of the Jewish Alliance, invited the research team – led by Fern Chertok and Daniel Parmer – to share their findings. More than 50 community members, including clergy and agency professionals, were present.

“The Town Hall Meeting served several purposes,” said Savit. “It brought people together, helped strengthen communal ties and promoted working jointly to tackle community problems.” To assure the audience of the reliability and credibility of the study, Chertok and Parmer explained that multiple research markers were employed. The findings analyzed the economic status of RI Jewish households, services currently available throughout the community and requests for assistance made to synagogues.

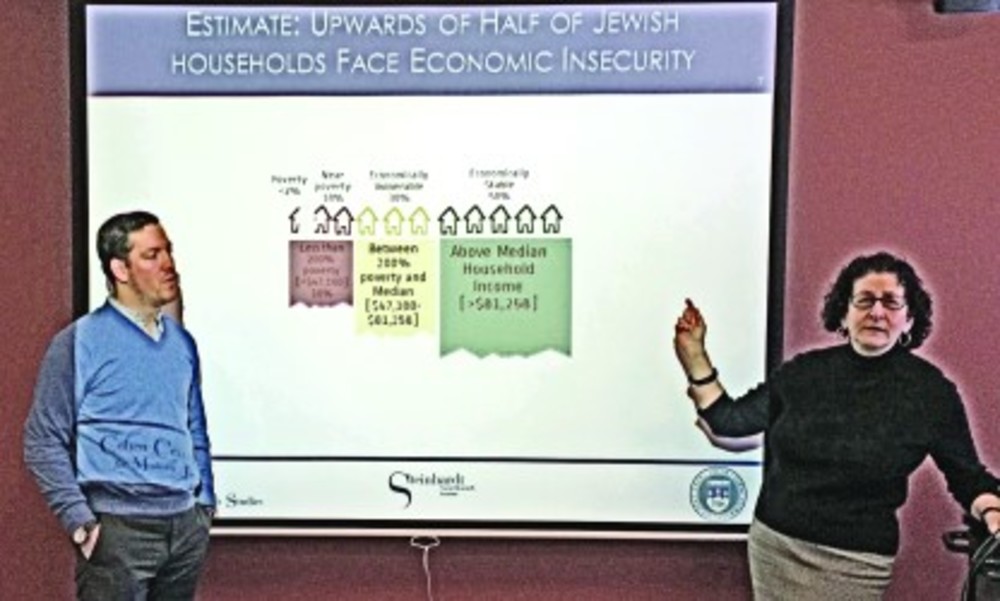

The research showed that two percent of Jewish households in the Alliance service area fall below the federal poverty guidelines. Another 18 percent live near poverty and 30 percent fall into the “economically vulnerable” category. This means that half of the Jewish households in communities served by the Alliance are financially fragile.

“This was a really important study, and we needed to understand it’s not just about poverty, but economic insecurity,” said Chertok, pointing out that state and federal programs provide for those who fall below government-defined criteria but not for those who live “on the edge.”

“But aren’t Jews different?” asked Parmer. Answering, he clarified, “Yes and no. Overall, American Jews are more educated and attain higher occupational levels; however, the gap in education and employment is narrowing, and there is little difference in the midrange of income when we compare Jews to other white non-Hispanics in the same communities. We’re comparing neighbors to neighbors.”

With fixed incomes, few employment opportunities and the rising cost of living, many Jewish Rhode Islanders find themselves caught in the clutches of economic vulnerability.

Jewish life, including synagogue membership, can be financially difficult for median household incomes, and families have to “stretch every dollar” to meet their basic expenses. “Even modest, unexpected household expenses or loss of hours at work can catapult a household into debt or delinquency,” said Chertok. “It became apparent to us that folks were living in economic insecurity and anything could set them over the edge.”

Readers might be surprised to learn that these are the people who do not look like a typical poor person. Chertok expounded, “They look good on paper; they own homes or rent; they drive cars, they have jobs.” However, after they add up expenses pertaining to their Jewish lives – synagogue membership, religious school, summer camp or Kosher dining – they are in trouble. The issue is, as Chertok says, “Jewish living is a luxury. It’s not something most families can afford, and that is really a problem.”

Interestingly, households seeking congregational assistance often make requests for $100 or less – enough to tide them over until the next paycheck. Congregation Beth Sholom’s Rabbi Barry Dolinger put it this way: “For me, the Brandeis study confirmed in data what I’ve experienced to be true since my arrival here in Rhode Island. Few are truly destitute, but so many are right on the brink of poverty. Judaism stresses compassion for those in need as perhaps the most important expression of authentic religious experience.”

Poverty and economic insecurity, of course, are not uniquely Jewish problems. However, the Alliance’s approach embodies Jewish values and traditions, such as preserving the dignity and communal engagement of those in need. “If half of our families are at risk for economic hardship,” Chertok advises, “the Jewish community needs to be in the business of prevention.”

Since the release of the Brandeis study, the Alliance continues to fund programs and services that support those living “on the edge,” and to create new solutions that address the issue of economic insecurity in Rhode Island. Judging by the ideas generated by the study, the Alliance is “on the edge” of something revolutionary.

Chertok and Palmer concluded their presentation with innovative recommendations for the Rhode Island Jewish community. They included teaching the Torah of giving and receiving help, creating a one-stop portal for accessing information and assistance, identifying resources for those on the margins, brokering job search services, establishing a chevre fund [see the JBoost article on page 19] and founding a forecast committee.

Afterward, attendees – professionals from partner agencies, lay leaders and rabbis – added to the conversation. Many were shocked at the findings. One audience member asked if the new initiatives would duplicate existing social services and if all the agencies were on board with the implementation of new resources. “There will be no duplication of services,” assured Savit. “The recommendations will buttress our existing social services. We have been speaking to everyone about this.” Susan Adler from the Kosher Food Pantry confirmed the dialogue between agencies and added, “I should be bombarded. Call us. If you need food, we deliver.”

Another attendee asked, “How as a community can we truly educate our community?” “Many people feel ashamed,” remarked Savit. “The point is not to be stigmatized,” he elaborated. “The challenge we have,” said Erin Minor of Jewish Family Service, “is that some people come to us because we are a Jewish agency and some people will not come to us because we are a Jewish agency.” “That is why teaching the Torah of giving and receiving is so important,” Chertok concluded.

“What do we need to do?” chimed Mark Ladin, a retired school principal. “Of your recommendations, what are the three most important?” “One: provide social service safety nets,” Savit began. “Two: promote self-sufficiency and vocational training. And three: remove barriers to Jewish living so that everyone has access to Jewish life.”

As the discussion continued, some members asked how they could participate in the endeavor. Savit challenged the town hall attendees to be more than just spectators. “We’re out there, raising funds [The Alliance has already secured $1.1 million of its $1.8 million goal.], but we also need volunteers. We’re looking for 125 individuals to donate their time – running errands, providing dental care, pro bono legal services, reading to children, etc.” One community member was quick to remark, “You contact me, and I’ll get people to recruit!” Volunteers are asked to contact Wendy Joering, Community Concierge at (401) 421-4111, ext. 169.

Savit’s final message to the crowd was that the Alliance is truly advocating for system change. “We have been investing in this [issue] for years and have partnered – and are proud to partner – with all agencies. I am grateful to so many of our colleagues here – from the rabbinical community to our partner agencies, to my Alliance colleagues. This is a community cooperative – a real kibbutz – and, yes, it takes a village.”

NOTE: FERN CHERTOK will also be speaking at Congregation Agudas Achim in Attleboro, MA, on Friday, January 31, at 7:30 p.m.

KARA MARZIALI is the director of communications at the Jewish Alliance.