Where do we come from?

“The image of the man and the woman in the perfect garden suggests a tension between things as they are and things as they might have been. It conveys a longing to be other than what we have become ….

“Something happened at the beginning of time – some history of decision, action and reaction – that led to the way we are, and if we want to understand the way we are, it is important to remember and retell this story.”

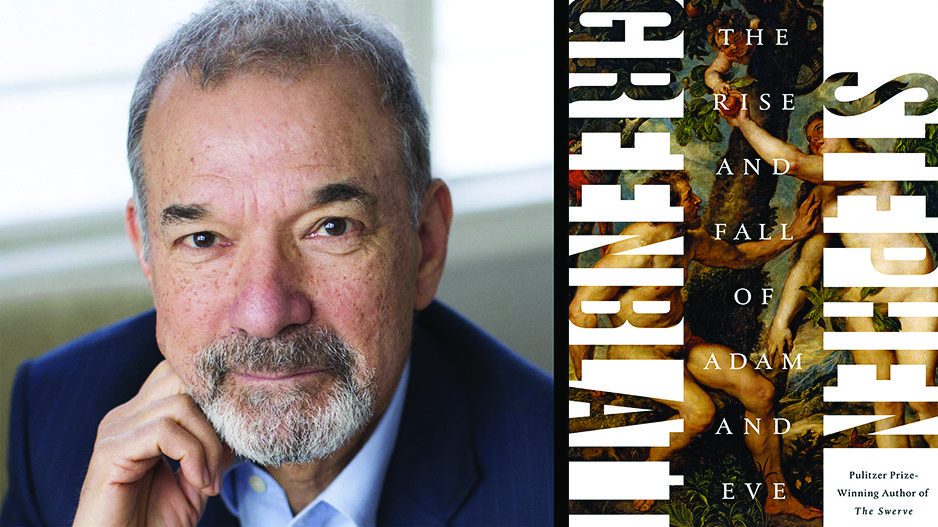

In his erudite and richly suggestive exploration of the origin story of our Western world, “The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve” (W.W. Norton & Company, 2017), Stephen Greenblatt takes the reader on a journey from the biblical book of Genesis through more than two millennia of interpretation and finally into the jungle of Uganda’s Kibale National Park, to observe our non-Edenic forbears, chimpanzees and bonobos.

Over the centuries, religious leaders, painters, sculptors, secular scholars, even today’s evolutionary biologists, have offered their reflections on the early chapters of Genesis, the first book of what we Jews call the TANAKH, or Hebrew Bible, and what Christians call the Old Testament.

We meet Adam and Eve for the first time in the paradise of the Garden of Eden in Chapters 2 and 3 of Genesis, in a text that overflows with ambiguity and contradictions. To begin with, we are told in Chapter 1 that God created both man and woman in the divine image by speaking them into existence; by way of contrast, we learn in Chapter 2 that God created Adam out of the clay of the earth (ahfar min ha’adamah) and then fashioned Eve from one of Adam’s ribs.

In the garden itself stand both the magical Tree of Life and the magical Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Adding to the pervasive sense of unreality is the talking snake, which manages to lure Eve into taking a bite of what turns out to be a poison fruit.

Of the many questions arising out of this myth of our origins, the most troubling centers on God punishing Adam and Eve for taking bites out of the forbidden fruit – a fruit that is never identified, but is usually taken to be an apple. Since God has consistently attempted to bar Adam and Eve from acquiring knowledge of good and evil – which they can only obtain by eating the apple – where is the justice in God punishing them for eating the apple before they have obtained the moral sense to know that it was wrong to do so? In effect, God seems to be condemning them for their state of innocence!

It turns out that though our Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament contain the identical text of the story of Adam and Eve – though the text, of course, appears in a wide variety of translations – the Jewish

and Christian traditions read our origin myth in profoundly different ways.

Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430) is the most influential of all Christian interpreters of these early chapters in Genesis. According to Augustine, eating of the apple was the Original Sin of disobedience to God’s command, the sin that has infected all future generations of our human family, bringing with it the catastrophic consequence of our mortality. From Augustine’s perspective, only the blood of Jesus Christ can wash away the stain of this Original Sin and transport the Christian believer from death to life eternal.

For complex psychological, spiritual and scriptural reasons, Augustine links this Original Sin to our sexuality. By the time he was in his mid-30s, he turned to a life of chastity so he might free himself from the burden, the distraction, the disruption of sexual desire.

As Greenblatt explains in his book, “Augustine did not want to live in a universe in which the moral reckoning would be left unpaid, in which human suffering meant nothing but the vulnerability of matter, in which wickedness would not be punished or exceptional piety receive an eternal reward. It was better to believe that accounts were being kept to the last scruple by an all-seeing God, even one who was murderously angry at humanity, rather than to believe that God was indifferent or absent.”

In contrast to the Christian notion of Original Sin – “In Adam’s fall, we sinned all” in the words of Colonial American Puritanism – Jewish tradition does not see us as born into a sinfulness passed on to generation after generation from the first man and the first woman. But neither do our rabbis see us as born in a state of pure goodness. Rather, we are born with competing drives, opposing tendencies: our yetzer tov, our inclination to do good, and our yetzer harah, our inclination to do evil.

The story of Adam and Eve does not weigh as heavily on our Jewish religious and moral imagination as it does for Christians. When we Jews do turn our gaze to the first man and woman, it is not to remind us of our moral failings but, more often than not, to remind us of the ethical optimism of our tradition, our capacity for brotherhood and sisterhood, as well as our deep appreciation for the unique worth of every individual.

We read in the Talmudic tractate Sanhedrin (38a): “Therefore Adam was created as a single individual … to provide harmony among God’s creatures, so that no person should say, ‘My father is greater than your father.’ … And to declare the greatness of God; for when a man mints numerous coins with a single stamp, they all look the same. But God stamps each person with the seal of Adam, and not one is like the other; therefore every one of us is entitled to say, ‘For my sake was the world created.’ ”

JAMES B. ROSENBERG is rabbi emeritus of Temple Habonim, in Barrington. Contact him at rabbiemeritus@templehabonim.org.